Who had died and whether they were important or not were questions that surgeons and barbers could easily answer in the days following the earthquake. Most of the victims died during the disaster itself, mainly from head injuries and bleeding, but many were saved by an amazing improvisational effort. On 3 November 3 1755, the king ordered the surgeons and nurses to treat the wounded, using medicine from the Royal Hospital of Todos os Santos. Surgeons assisted the nobles as well as the anonymous, helping to treat infections which were the cause of most deaths. For the next seven days, many injured survivors were rescued from the rubble. Even the ninth day after the earthquake, a girl was rescued, still alive. Hospitals recorded who was injured and what injuries they had, providing specific information about what limb was broken and what type of would they had. This created a wealth of information unlike any other for the time.

Surgeons and doctors had their work cut out for them, all the while working under chaotic conditions. It was so bad that many days later, on 18 December 1755, patients had almost died in Rossio because the heavy rains had caused flooding. Lisbon was in a state of chaos for long after the quake itself. At first, the sick and injured were assisted in the gardens of private palaces, in the cellars of the Count of Castelo Melhor or simply among the ruins. In February 1756, they started sending them to the Royal Hospital of Todos os Santos, which was still in very poor condition. There were too many victims to be counted so many were sent to São Bento Monastery, forcing the surgeons to work tirelessly for months.

The surgeon is concerned about the rumors about the earthquake. Some say that the damage was not as serious and that the number of dead was lower. The news is vague and inaccurate. The abounding fear was why observations needed to be serious. Some people made mountains of molehills, but nobody forgets the people burnt alive or buried.

In fact, the earthquake and its multitude of casualties contributed greatly to the understanding of the precarious state of medical education in Portugal. Portuguese surgeons were described as obsessed with bloodletting, although they were considered skilled. The famous professor of medicine Bernardo Santucci had been criticized for his insistence on dissecting corpses and for the large number of clinical autopsies performed. The rigorous examination of the causes of death contributed to finding the root of the evil at the origin of the diseases or trauma. In fact, the anatomy and surgery courses given at the Hospital de Todos os Santos, in Rossio, helped save lives and it can be said that the earthquake was one of the main springboards triggering an evolution in medical education.

IN SALA DOS CONTOS:

Surgeon with a license from Hospital de Todos os Santos in Lisbon. Although the Church and the king sometimes forbade it, he studied anatomy and surgery on real corpses. The surgeon tells:

After my medical studies in Coimbra, I managed to get my Surgeon’s license in Lisbon, where Bleeding Barbers are also taught. Bleeding is a common remedy, and a way to deal with many afflictions.

On the day of the earthquake, I went straight to Rossio, where many of the wounded were taken and where they stayed inside tents for the next three weeks, as the Hospital de Todos os Santos was not yet safe. Apart from the destruction caused by the earthquake, the hospital had partially burned down years before... I even fear that it will never be fully functional again. Since that day, I have had no rest. When I am not working in the hospital, I travel to the city outskirts with noblemen and charitable people to treat other wounded people and their resulting infections, the greatest cause of death.

Even days after the quake, we were still pulling survivors out from under the rubble. A girl was rescued nine days after! Imagine spending nine days in the dark, not knowing whether someone will find you!

We have all been working nonstop for weeks. There is one good thing about this tragedy: the number of wounded caused by the earthquake shows how precarious our medical education is in Lisbon. After all, my old professor, Santucci, was right. People are now starting to understand what he meant when he would say that autopsies were necessary “to find the root of evil, and to know its cause”.

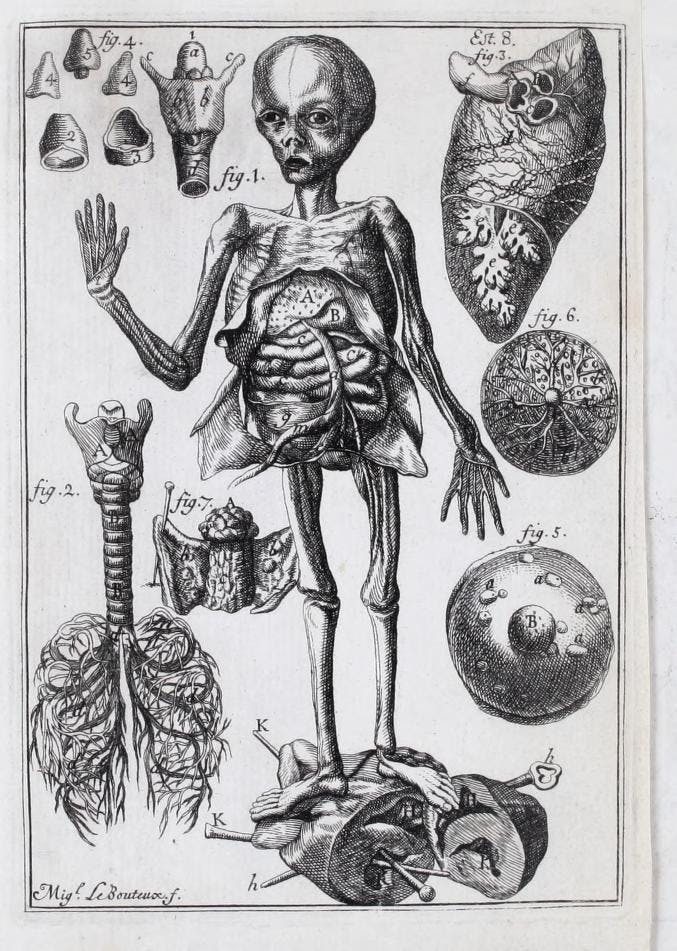

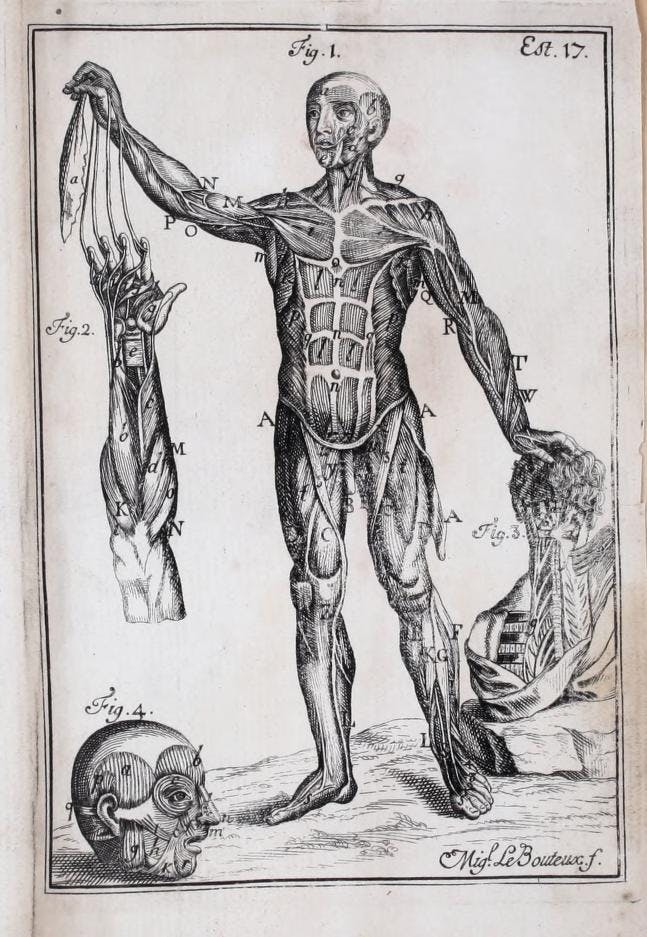

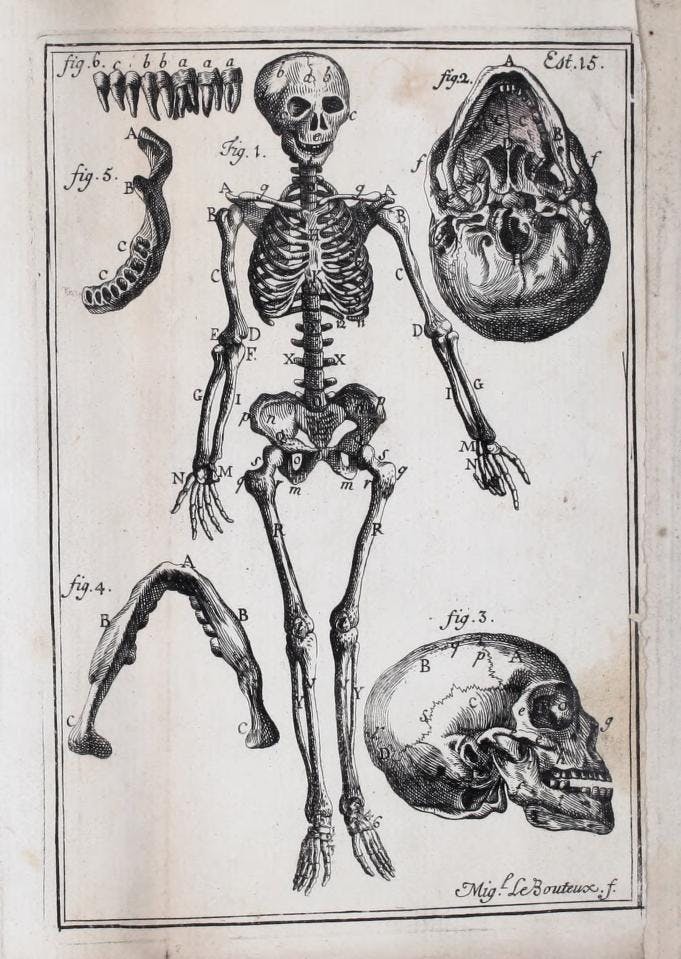

The anatomical drawings (engraved by Michel Le Bouteux) in the book “Anatomy of the human body: compiled with medical, chemical, philosophical and mathematical doctrines,” by Bernardo Santucci, Doctor at the University of Bologna and Professor of Anatomy at the Royal Hospital of All Saints, showed the evolution of Italian medicine, in the rigour of the physiological and anatomical descriptions, in the first half of the 18th century.

Bibliography

Laurinda ABREU, A politica religiosa do Marquês de Pombal: algumas leis que abalaram a Igreja, Separata da Revista Século XVIII, vol. I, tomo I, Lisboa, 2000, pp. 223-233.

Laurinda ABREU, A assistência e a saúde como espaços de inovação: alguns exemplos portugueses, Lisboa, Gradiva, 2008.

Laurinda ABREU, «O terramoto de 1755 e o Breve do papa Bento XIV», O terramoto de 1755: impactos históricos, Ana Cristina ARAÚJO e José Luís CARDOSO, Livros Horizonte, 2013, pp. 237-247.

Boaventura Maciel ARANHA, Cuidados na vida e descuidos na morte, Officina Pinheirense da Musica, 1743.

Ana Cristina ARAÚJO, A Morte em Lisboa: Atitudes e Representações 1700-1830, Livros Horizonte, 1997.

Miguel Telles ANTUNES, «Vítimas do Terramoto de 1755 no Convento de Jesus», Revista Electrónica de Ciências da Terra, vol. 3, nº 1, 2006, pp. 1-14.

Helena Carvalhão BUESCU, «Sobreviver à catástrofe: sem tecto, entre ruínas», O Grande Terramoto de Lisboa», Ficar Diferente, Helena Carvalhão and Cordeiro, Gonçalo (eds), Gradiva, 2005, pp. 19-72.

Juizo verdadeiro sobre a carta contra os medicos, cirurgioens, e boticarios ha pouco impressa com o titulo 'Sustos da vida nos perigos da cura', exposto em huma carta de hum amigo a outro, que sobre ella pedio o parecer. Lisboa: Na Officina de Joseph Filipe, 1758.

Maria Amélia Dias FERREIRA, O socorro às vitimas do terramoto de Lisboa: 1755, Tese de Doutoramento em Enfermagem, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, 2016.

Maria Luísa Pedroso de LIMA, «Tragédia, risco e controlo: uma releitura psico-social dos testamentos de 1755», Análise Social, vol. XLIII (1.º), 2008, pp. 7-28.

Joachim Joseph Moreira de MENDONÇA, História universal dos terremotos, que tem havido no mundo, de que ha noticia, desde a sua creação até ao século presente, Officina de Antonio Vicente da Silva, 1758.

Antonio dos REMÉDIOS, Resposta à Carta de Joze de Oliveira Trovam e Sousa, Lisboa, na Offi. de Domingos Rodrigues, 1756.

Bernardo SANTUCCI, Anatomia do corpo humano, recopilada com doutrinas medicas, chimicas, filosoficas, mathematicas, com indices, e estampas, representantes todas as partes do corpo humano Lisboa, Officina de Antonio Pedrozo Galram, 1739.

Luis A. de Oliveira RAMOS, «Do Hospital Real de Todos os Santos à História Hospitalar Portuguesa», Revista da Faculdade de Letras, II Série, vol. X., 1993, pp. 334-350.

António Nunes Ribeiro SANCHES, Tratado da Conservaçam da Saúde dos Povos, Officina de Joseph Filippe, 1757.

Fr. Diogo SANTIAGO, Postilla Religiosa e Arte de Enfermeiros, Officina de Miguel Manescal da Costa, 1741.

Jose Acúrsio de TAVARES, Verdade Vindicada ou resposta a huma carta escrita em Coimbra, em que se dá noticia do lamentável sucesso de Lisboa, no dia I de Novembro de 1755, Lisboa, Na Officina de Miguel Manescal da Costa, 1756.