In 1755, Lisbon was a Babylon of ships and goods. The many different territories under Portuguese rule brought an amazing plethora of products to the streets of Lisbon, but it was still slave work that kept the empire in motion. Indeed, it was the only labour force capable of producing the gigantic quantities of sugar and gold, the two products that fed all the trade routes of the time. In this way, the triangular trade of the 16th and 17th centuries—between Lisbon, Rio de Janeiro, and Angola—became a much more complicated system in the 18th century. Stop-over voyages, with the famous India Route (towards the East) and the Gold Fleets (towards Brazil) kept the goods in perpetual movement. Indian cloth was exchanged for enslaved men and women in the ports on the Gold Coast (Saint Jorge da Mina, now Ghana), in Benguela and Luanda (Angola) or on the Island of Saint Tomé. Enslaved people were sent to Brazil to work in gold mines and on sugar cane plantations. Ivory and gold were brought from the interior of Mozambique, in the heart of Africa, to be exchanged in India for cloth, bracelets, and funerary ornaments. Thus the circuit took on a life of its own, until it was out of the control of the Crown, with gigantic amounts of contraband.

This trade produced an incalculable amount of business and so the Crown sought to control the process through Companies. But it was difficult to curb the multiple trades, mainly due to the costs of patrolling the seas and keeping up with the technological development of English and Dutch warships.

In the East, despite being harassed, the Portuguese maintained a large number of old trading posts and forts, sometimes ruined, from the east coast of Africa to the China Sea. Portuguese was the language of business, but it was also synonymous with gunpowder and destruction. There were a few territories left in Timor, Sunda, and the Solor Islands and, above all, Goa, Damão, and Diu—the old jewels of a lost Crown. Ships went to Goa only a few times a year, sometimes not even once a year. Diu, on the Gulf of Cambia brought carpets and furniture with inlays and cotton blankets and other products came from Persia. Goa brought diamonds, rubies, pearls, cinnamon, and pepper. With their republic of merchants, the city of Macao, in the Empire of China, contacts were more intense. Silks and cloths, porcelain, various teas, copper, and ambergris were bought.

Given the complexity of these trade relations, the king's ministers spoke of the empire as a system of spindles and cogs, and despaired at this uncontrollable machine. Some understood wealth as a product of the profit margins of trade, others wanted to increase the efficiency of agriculture, others still called for attention to the costs of the slave trade, which was becoming increasingly unpopular.

However, there was no doubt in 1755, that Brazil was the heart of the empire and the wealth of the kingdom of Portugal. In addition to huge amounts of gold, Brazil supplied sugar, brazilwood, leather, tobacco, cocoa, chocolate, diamonds and other precious stones, indigo, and spices such as pepper, ginger and a kind of cinnamon flavoured nutmeg. Cotton from the Amazon was used to clothe enslaved women and men. The very name of Brazil derives from the first product of the American continent mass-traded by the Portuguese—the pau-brasil (brazilwood), known for its orange hue, similar to burning coals.

These products may not have always transited through Lisbon, but the king received taxes for all the products that were traded throughout the far-reaching territories under Portuguese rule. The wide array of products that were brought to Lisbon gave the city a seductive, oriental feel that remains to this day. The golden carriages and sumptuous palaces, churches, and convents were proof of how much the city and its people benefited from the impressive flow of goods.

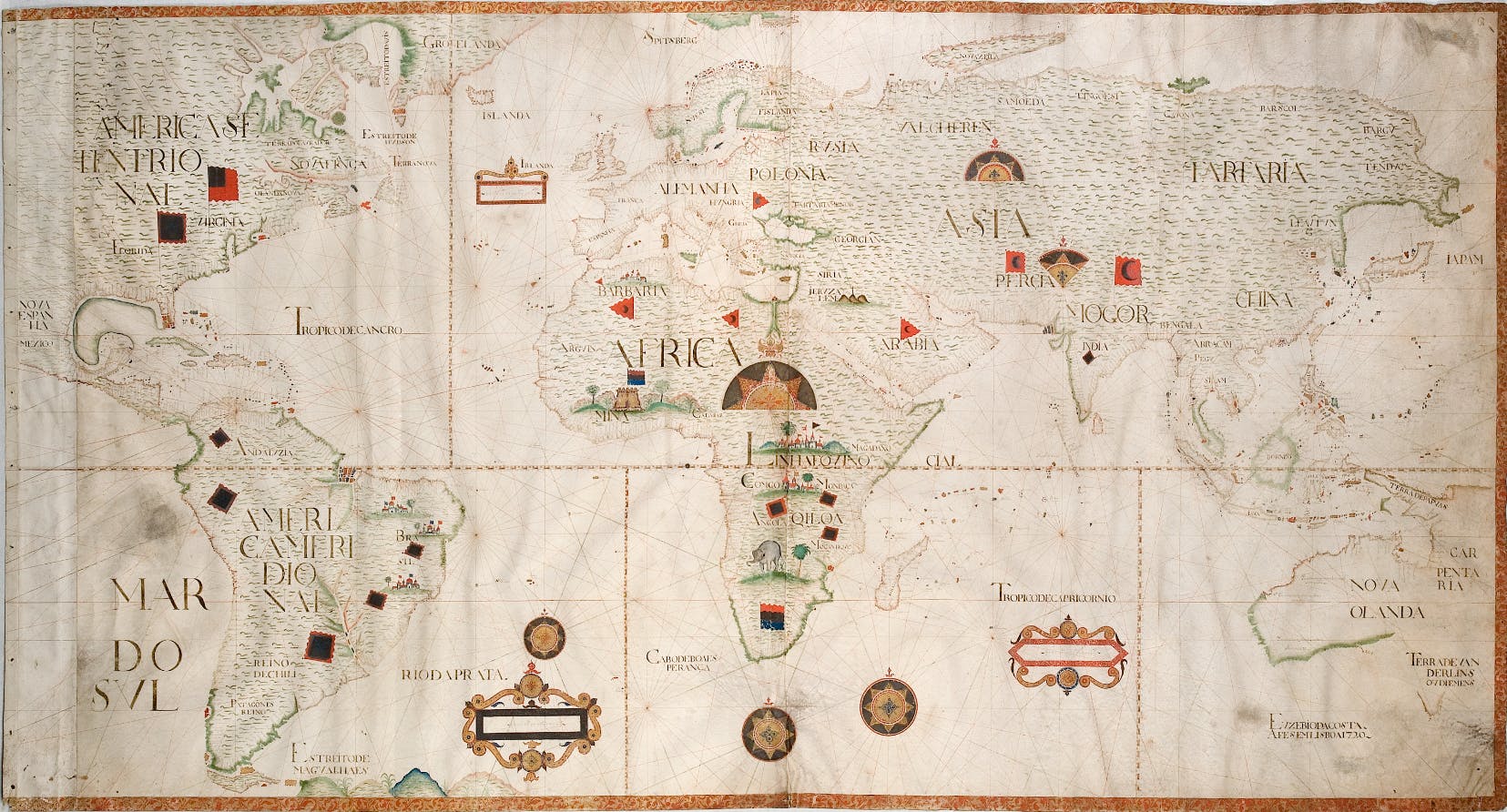

Nautical charts, or portulans, became an essential tool for navigators, allowing a more precise knowledge of their position, thanks to the development of astronomical tables and instruments for measuring the position of the stars. These maps were not only working tools but sometimes also propaganda tools, showing the influence of the kingdoms on the known world. This 1720 planisphere fulfils both functions. Note how the Portuguese world is recognizable, while other places less explored and less critical for Portugal are only vaguely evoked.

“In 1755, Lisbon was a Babylon of ships and goods.”- Lisbon seen from Marquês de Abrantes Palace (18th century, 1st half) – Oil on canvas, unknown autor. Colecção doMuseu de Lisboa /Câmara Municipal de Lisboa - EGEAC

Continue Exploring

Bibliography

Dauril ALDEN, Royal Government in Colonial Brazil: With Special Reference to the Administration of the Marquis of Lavradio, Viceroy, 1769-1779, University of California Press, 1968.

Charles Ralph BOXER, The golden age of Brazil 1695-1750: growing pains of a colonial society, University of California Press, 1962. The Golden Age of Brazil, 16591750 Growing Pains of a Colonial Society : Charles R. Boxer : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Francisco BETHENCOURT e Diogo Ramada CURTO (orgs.), A expansão marítima portuguesa, Edições 70, 2010

Ângelo Alves CARRARA, Receitas e despesas da Real Fazenda no Brasil: século XVIII, UFJF, 2009.

H.E.S FISHER, The Portugal Trade: A study of Anglo-Portugeuse Commerce 1700-1770, London, 1971.

Júnia Ferreira FURTADO, Homens de negócio: a interiorização da metrópole e do comércio nas Minas setecentistas, HUCITEC, 1999.

Vitorino Magalháes GODINHO, Prix et monnaies au Portugal (1750-1850), Armand-Colin, 1955.

Vitorino Magalhaes GODINHO, «Portugal, as frotas do acncar e as frotas do ouro (1670- 1770)», Ensaios II, Sobre História de Portugal, Livraria Sá da Costa, 1968, p. 295- 315.

Roberto do Amaral LAPA, A Bahia e a Carreira da India, Companhia Editora Nacional, 1968.

Jorge Borges de MACEDO, O Marquês de Pombal. 1699-1782, Biblioteca Nacional, Série Pombalina, 1982.

Joaquim Romero MAGALHÃES, O Algarve Econômico, 1600-1773, Estampa,1993.

Kenneth MAXWEELL, Conflicts and Conspiracies: Brazil and Portugal 1750-1808, Cambridge University Press,1973.

Michel MORINEAU, Incroyables Gazettes et Fabuleux Mitaux, Cambridge University Press/ Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, 1985.

Fernando NOVAIS, Portugal e o Brasil na Crise do Antigo Sistema Colonial, HUCITEC, 1986.

Jorge PEDREIRA, Estrutura industrial e mercado colonial. Portugal e Brasil (1780-1930), Difel, 1994.

Virgílio Noya PINTO, O ouro brasileiro e o comércio anglo-português, Uma contribuição aos estudos da economia atlântica no século XVIII, Companhia Editora Nacional – Brasiliana, 1979.

Isabel dos Guimarães SÁ, Quando o rico se faz pobre: Misericórdias, caridade e poder no império português 1500-1800, Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, 1997.

Lilia Moritz SCHWARC, Paulo César de AZEVEDO e Angela Marques da COSTA, A longa viagem da biblioteca os reis, Do terremoto de Lisboa à Independência do Brasil, Lisboa, Companhia das Letras, 2002

Stuart B. SCHWARTZ, Segredos internos: engenhos e escravos na sociedade colonial,1550 – 1835, Companhia das Letras, 1988.

Fernando TOMAZ, «As finanças do Estado Pombalino: 1762-1776», Estudos e Ensaios em Homenagem a Vitorino Magalhães Godinho, 1988, pp. 355-388.