Shortly after the earthquake, in 1756, famous articles about the Lisbon earthquake were published in German by a certain Immanuel Kant, a then-unknown scholar. His interest could be likened to the question in the Inquérito about how and in what direction buildings fell and the earth moved during the quake. But were the explanations given as to what caused the earthquake bound to be the same, whether they were written by a Portuguese or German scholar?

Reading Kant, readers would understand that earthquakes were explained by the particular shape of the ground. Caves, mines, and underground labyrinths explain why the earth so easily collapsed. The tremors propagated in a kind of implosion through the abundance of caves along the banks of the rivers.

However, these were not very solid explanations.

That is why a Portuguese text of the time admitted that of all natural phenomena, earthquakes were the most difficult to explain. But what exactly was meant by “earthquake” back then? “A pulsation, tremor, tilt, or upheaval of the earth in some part of the globe,” answered a curious guesser in 1756. At the time, main ideas about the origin of earthquakes were still based on classical philosophy. The fermentation of inflammable materials in underground caverns caused volcanoes. But, as was understood at the time, it was the absence of volcanoes—through which explosive matter would have been expelled—and the corresponding accumulation of pressure that caused earthquakes.

The experience of the Lisbon earthquake in 1755 contributed to a better understanding of the issue. The close relationships travellers, businessmen, scientists, doctors, and clerics had favoured the circulation of ideas. In this respect, the German community in Lisbon played an important role. Germans were associated with technological professions: They were printers, glassmakers, bookbinders, gunsmiths, and many were financiers and merchants. In 1755, the many German survivors of the disaster, including a Bible translator who owned a collection of Portuguese literature, encouraged the flow of ideas between Lisbon and Hamburg. Science broke down political and religious barriers. The Hamburg Senate also showed great solidarity by sending the equivalent of 900,000 reals and four ships, each loaded with 200 tonnes of wood for the reconstruction.

In fact, there are many testimonies of this scientific spirit, which circulated between different countries and were copied in other cities. There are descriptions of earth movements in Lisbon on that fateful day that are likened to being on a boat. According to these testimonies, there was no doubt that the largest and longest movements had occurred in a north-south direction. More rigorous descriptions led to better explanations. Merchants, who watched fleets on the river, were privileged witnesses of the ebb of the sea, giving never-seen-before views of the depths of the sea with the movement of the tides. Similarly, they recorded the various movements of the earth, for nothing could disturb confidence in trade more than the 250 or so tremors recorded in the six months following 1 November 1755.

IN SALA DOS CONTOS:

A German merchant living in Lisbon: Born in Hamburg and a correspondent in Lisbon, he collects scientific instruments and is curious about logical and rational explanations of earthquakes. After the earthquake, he writes home:

My Dearest Parents,

Hope this letter finds you in good health. I am doing well under the circumstances; though I still do not understand why God has spared me and why I have survived the earthquake that shattered this city. On the 1st of November, I was tempted by the beauty of the morning to take a stroll, so I left my office and went to the top of St. George’s Hill. That might have been my salvation, as the plateau there is wide and free of buildings. Suddenly, the shaking started. I didn’t quite understand what was happening, but by the third shake, and as I hung onto a pole for dear life, I knew that I would be lucky to survive.

When the ground stopped shaking, and as I walked down from the hill, I understood the extent of the damage. No words can express the horror. Dust and smoke from the fires surrounded me, and I could barely breathe. Darkness was around me, and I found myself surrounded by a city falling into ruin, with crowds of people screaming and calling out for mercy. This city will never be able to recover!

I have found refuge in the garden of another merchant’s house. With many other survivors, I have been sleeping in tents. I feel safer with no walls around me! Everyone is scared another earthquake will hit again and destroy what little is left.

Of course, I am sure another will hit soon. I had the good fortune of secretly reading an article published in the weekly Königsberg newspaper by a young scholar named Immanuel Kant. He asserts that earthquakes are caused by implosions occurring in the ground, near rivers, just like in Lisbon. The ground here is filled with caves, mines, and labyrinths that often fill with water from the ocean and rivers. The king and his ministers are debating whether to rebuild Lisbon or move the royal court to Belém…Rumours are that the city will indeed be rebuilt in the same area where I’m sure another earthquake is bound to happen!

That’s why I’ve decided to come back home soon and for good. I do not wish to experience this again in my lifetime. I have asked the main office for permission to leave Lisbon, and I am now preparing everything for when my substitute arrives. May God make it sooner than later!

I hope the winter is not too harsh back home and that you are in good health.

Your loving son,

xxx

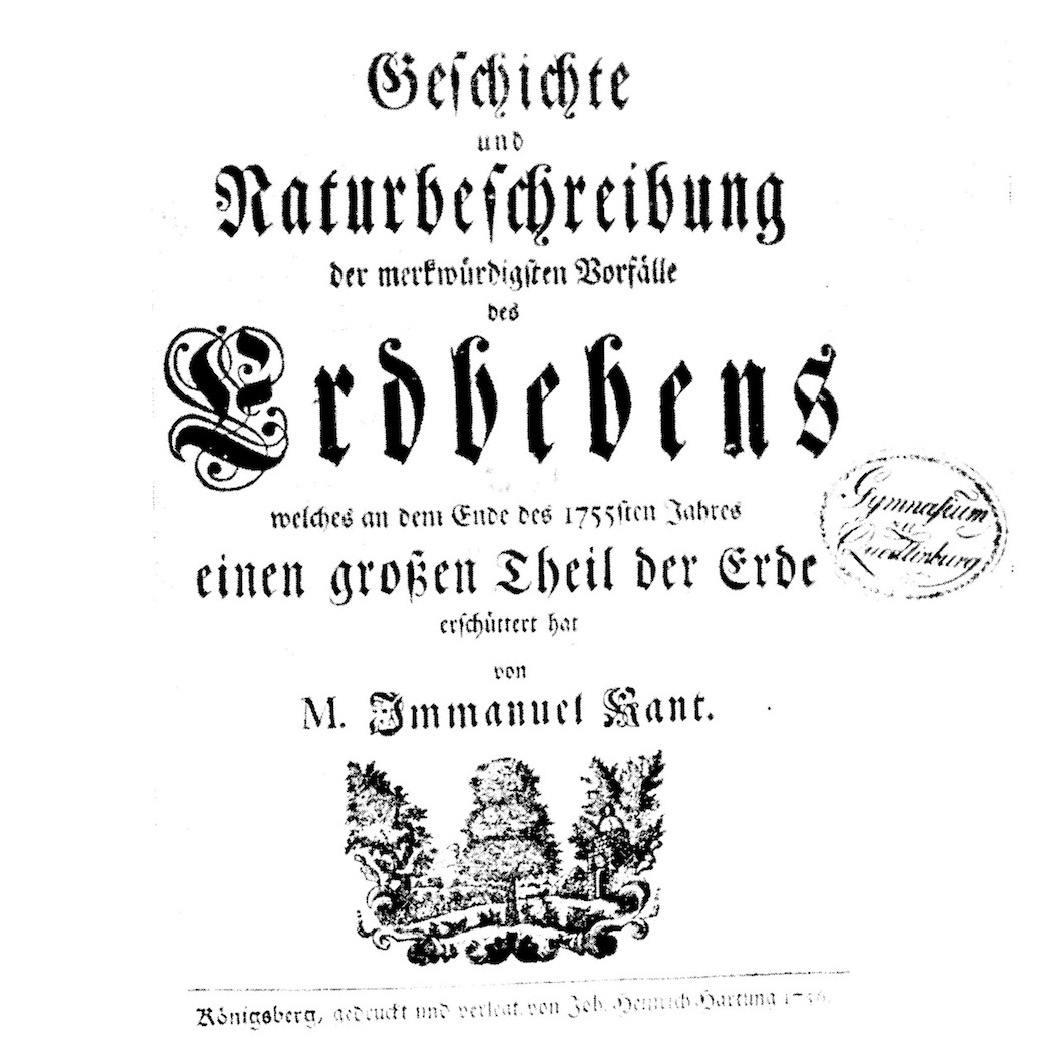

Kant’s publications on the Koninsberger newpaper:

- Jan. 1756 “On the Causes of the Earthquakes, on the Occasion of the Calamity that befell the Western Countries of Europe towards the End of Last Year.”

- Feb. 1756 “History and Natural Description of the Most Noteworthy Occurrences of the Earthquake that Struck a Large Part of the Earth at the End of the Year 1755.”

- April 1756 “Continued Observations of the Terrestrial Convulsions that have been Perceived for Some Time.”

These three essays were written in response to the Lisbon earthquake of 1 November 1755, which destroyed more than half the city and killed tens of thousands of its inhabitants. The science of tectonic plates was still far away, and Kant's scientific explanation of the causes of the earthquake was very much based on the natural philosophy of Aristotle and ancient philosophers, where the effects of combustion and underground cavities were pointed out as dominant factors. But Kant's main point was that the earthquake should be understood in entirely physical terms. He rejected the catastrophe as an affront to divine goodness or an exemplary punishment from the Creator. The fact that these essays were intended for a wide audience was far more revolutionary than it may seem today. In that sense, Kant was pointing to a new way of thinking.

Places to visit

- Museu de LisboaExplore

Continue Exploring

Kant, Immanuel: Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels. Königsberg u. a., 1755:

https://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/book/show/kant_naturgeschichte_1755

Bibliography

Ana Cristina ARAÚJO, «O desastre de Lisboa e a opinião pública europeia», Estudos de História Contemporânea Portuguesa - Homenagem a Victor de Sá, Livros Horizonte, 1991, pp. 93-107.

Maria Luísa BRAGA, «Polémica dos terramotos em Portugal», Cultura-História e Filosofia, Vol. V, 1986, pp. 545-573.

Pedro CALAFATE, «A polémica em torno das causas do terramoto de 1755», História do Pensamento Filosófico Português, Pedro Calafate (dir.), Vol. III, 2002, pp. 369-381.

Rómulo de CARVALHO, «As interpretações dadas, na época, às causas do terramoto de 1 de Novembro de 1755», Memórias da Academia das Ciências de Lisboa, Separata do Tomo XXVIII, 1987, pp. 179-205. https://purl.pt/12157/1/estudos/terramoto.html

João José Alves DIAS, «A colónia alemã de Lisboa face à Inquisição: um olhar sobre o século XVI», Portugal – Alemanha: Memórias e Imaginários, Maria Manuela Gouveia DELILLE (Coordenação), Minerva – Centro Interuniversitário de Estudos Germanísticos, 2007, pp. 75-82.

Russel R. DYNES, «The Dialogue between Voltaire and Rousseau on the Lisbon Earthquake: The Emergence of a Social Science View», International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 18,1, 2000, pp. 97–115.

John FLAMSTEED, A letter concerning earthquakes, Londo, Printed for A. Millar, 1750. https://archive.org/details/b30374170_0002

Bernd HAMACHER, «Strategien narrativen Katastrophenmanagements: Goethe und die "Erfindung" des Erdbebens von Lissabon», Das Erdbeben von Lissabon und der Katastrophendiskurs im 18. Jahrhundert, Gerhard LAUER et al. (ed.), 2008, pp. 162–172.

Isidoro ORTIZ GALLARDOS, Lecciones entretenidas y curiosas physico-astrologicometheorologicas sobre la generación, causas y señales de los Terremotos, Salamanca, Antonio Joseph Villargordo, 1756.

Francisco Xavier de OLIVEIRA Discours pathétique au sujet des calamités presentes arrivées au Portugal (...), Londres, 1756.

Francisco Xavier de OLIVEIRA, Tratado do princípio, progresso, duraçam e reino do reynado do Anti-Cristo, oferecido à nação portuguesa (...), Londres, 1768.

António PEREIRA, Commentario Latino e Portuguez sobre o terramoto e incendio de Lisboa de que soy testemunha ocular, Na oficina de Miguel Rodrigues, 1756.

Jean-Paul POIRIER, «The 1755 Lisbon disaster, the earthquake that shook Europe», European Review, nº 14, Cambrigde University Press, 2006, pp. 169-180.

Relation du désastre arrivé aux villes de Lima, & du Callao, au Pérou; le 28 octobre 1746, par un tremblement de terre, Paris, 1747.

Maria Fernanda ROLLO, Ana Isabel BUESCU e Pedro CARDIM, História e ciência da catástrofe, Edições Colibri, 2007.

Jean-Jacques ROUSSEAU, «Lettre de J. J. Rousseau à M. de Voltaire, le 18 Août 1756», Œuvres complètes, Gallimard, La Pléiade, tome IV, 1969, pp. 1057-1075.

Frei Francisco António de SÃO JOSEPH, Discurso moral sobre os tremores que causou o terramoto na gente de Lisboa, Lisboa, 1756.

Joseph Alvarez da SILVA, Investigação das causas proximas do Terramoto, sucedido em Lisboa no ano de 1755, Lisboa, 1756.

John SHOWER, Practical reflections on the earthquakes that have happened in Europe and America but chiefly in the islands of Jamaica, England, Sicily, Malta, &c. With a particular and historical account of them, and divers other earthquakes, Printed and sold at Cook, James, and Kingman, Londo, 1750. https://archive.org/details/b30355588

William STUKELEY, The philosophy of earthquakes, natural and religious: Or An inquiry into their cause, and their purpose, Printed for A. and C. Corbett, London, 1756.

Rui TAVARES, O pequeno livro do grande terramoto, Tinta da China, 2005.

VOLTAIRE, «Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne, ou examen de cet axiome: Tout est bien», Mélanges, Gallimard, collection Pléiade, 1961. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5727289v/f9.image#