The 1755 earthquake had flattened the city of Lisbon, where the Court of Portugal resided; a kingdom without a Parliament. The king ruled, aided by his counselors consisting of a few ministers and three secretaries of state chosen from among the leading ecclesiastics, aristocrats, advisors, or jurists. At the time, the king was still inexperienced in the arcana of court politics. There were also tensions between the main secretaries, and one of them was already old and sick. On the evening of 1 November 1755—when the tremors had ceased, the waters had receded, and the fire had subsided—seeing his city destroyed, one man’s political instincts were triggered. That man was one of the secretaries of state Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo (later Count of Oeiras and made Marquis of Pombal in 1769). It was a serendipitous moment where the king’s incapacitated government encountered the secretary of state’s incredible intelligence and unrivalled ambition. He drove through the streets of the city on the evening of 1 November in his carriage, and over the next few days, as the rubble receded, a new order emerged from the ruins. Witnesses at the time said Sebastião José would sleep and eat in his carriage, drinking only a broth that his wife brought him the first two days. Supported by the leading ministers of the Court, he took power into his own hands, as the terror caused by this furious eruption of nature, had left a staggering void. Three major actions motivated his political project: To understand the earthquake (Inquérito, or Inquiry), to restore order (Providências, or emergency measures), and to rebuild the city by introducing a new rationale (Lisbon Plan).

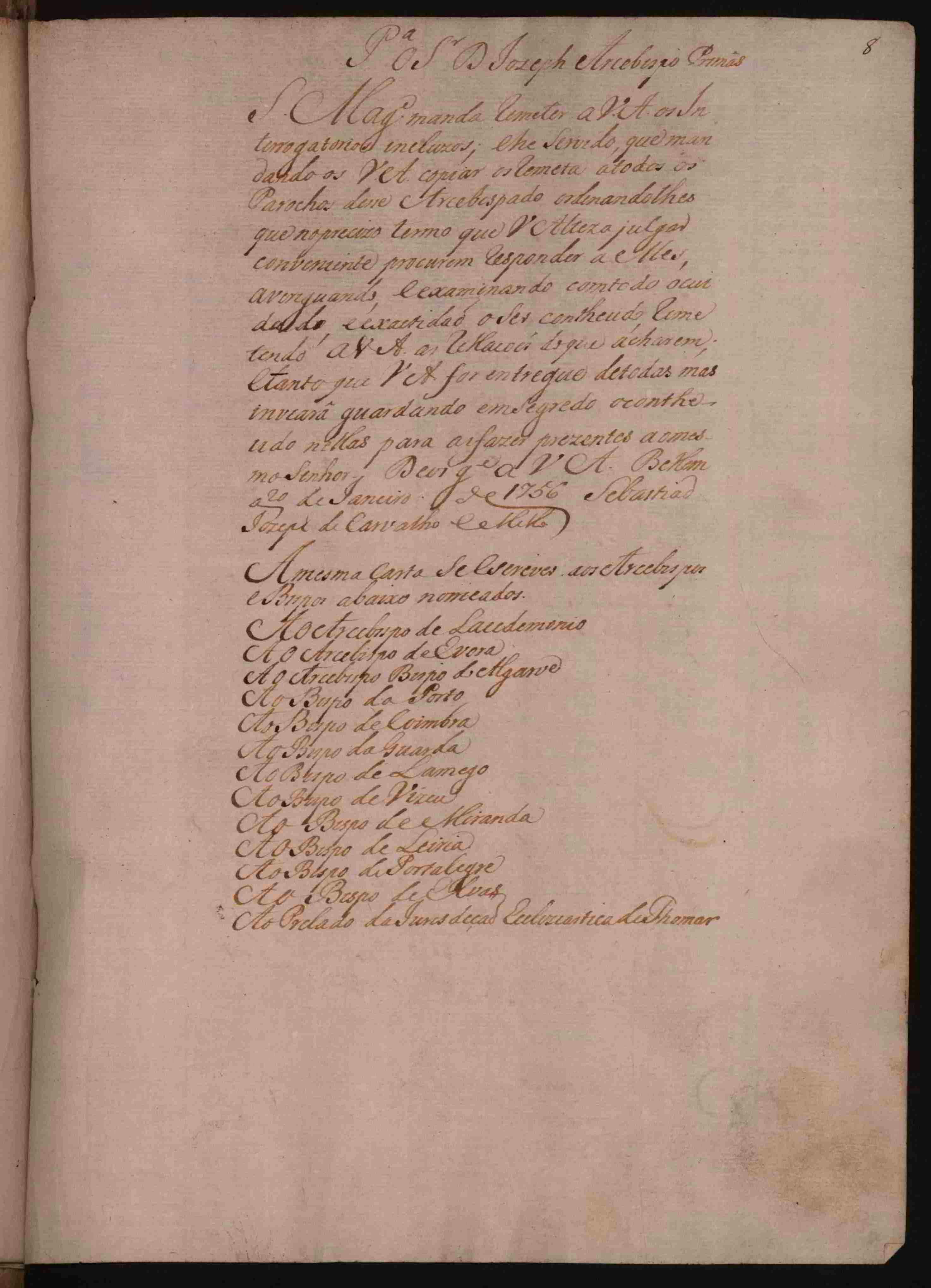

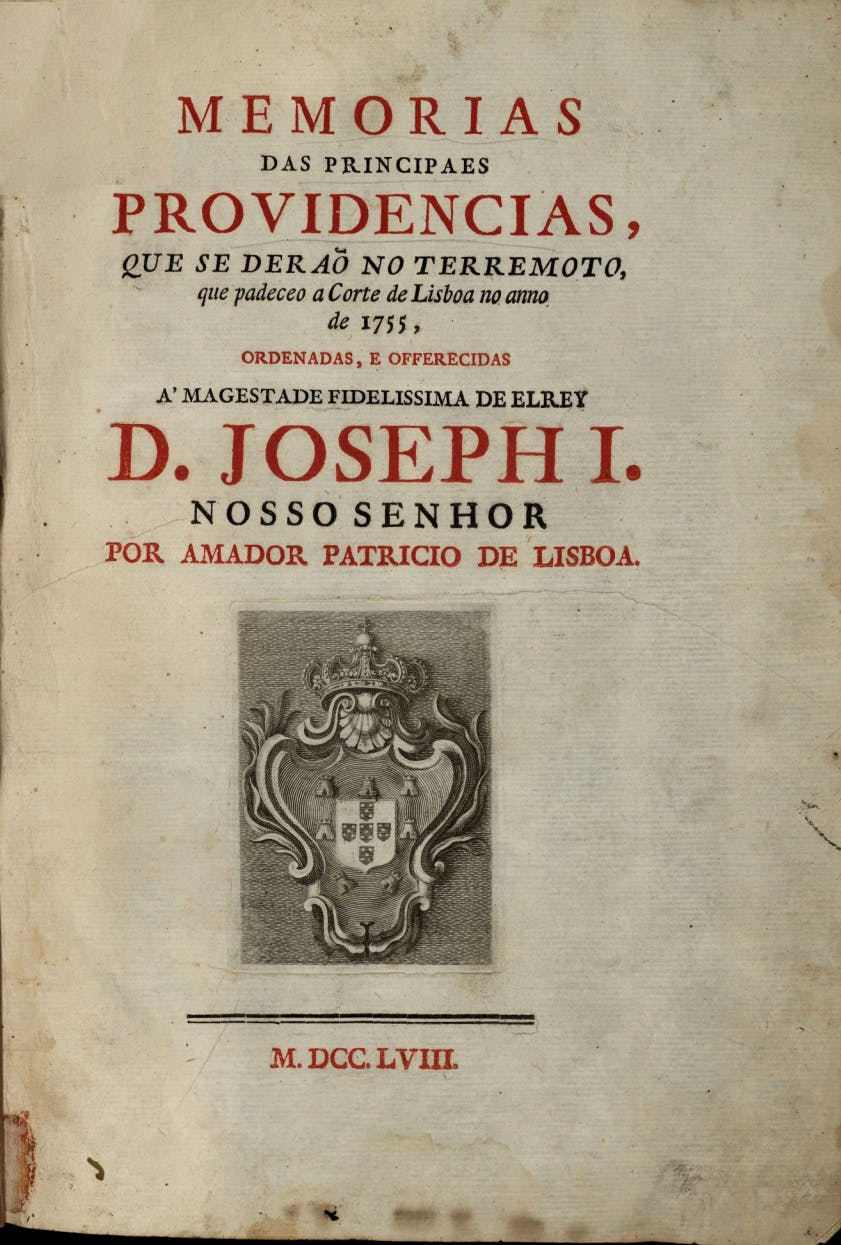

The Inquiry, sent to the bishops of the kingdom, attempted to understand the impacts of the disaster and its natural manifestations. The emergency measures were the result of feverish activity, aimed at bringing life back to the city of Lisbon: Carvalho e Melo signed 130 decisions in 8 days. The king's various ministers became the executors of a policy guided by an unstoppable logic: Time and money needed to be saved, and nothing was to be done twice. Finally, the court commissioned and then studied the drawings and plans of the city to make the dream of rebuilding the city a reality—organising traffic arteries, waste disposal, building security, and new property rights. This reconstruction, designed by the chief engineer and carefully piloted by the secretary Sebastião José, lasted throughout the second half of the eighteenth century. These three guidelines relied on the coordination of thousands of people and allowed a completely new city to emerge from the ruins—both in terms of the aesthetics of its facades and the foundations for urban planning implemented—placing symmetry and standardisation at the heart of the lower city of Lisbon.

Faced with the destructive force of natural phenomena, a Portuguese poem of the time put all humans on the same level: “General, priest, layman, monk / All victims of the fatal calamity / Minister, poor, rich, gentleman / Merchant, soldier, day laborer / Miserable, happy, bored / It is to all that speaks such a trembling moan / The same for all, a weight for all / In this bitter clamor of nature.” A terrible equality that reveals the power of nature and the benefits and risks of using planning, reasoning, and cooperation to organise cities. Perhaps this is why Sebastião José, who had become Marquis of Pombal in the meantime, was credited with penning a political speech on the advantages that the kingdom of Portugal could derive from its misfortune, on the occasion of the earthquake of 1 November 1755, thus justifying his policies in response to the great catastrophe, which is impressive even today.

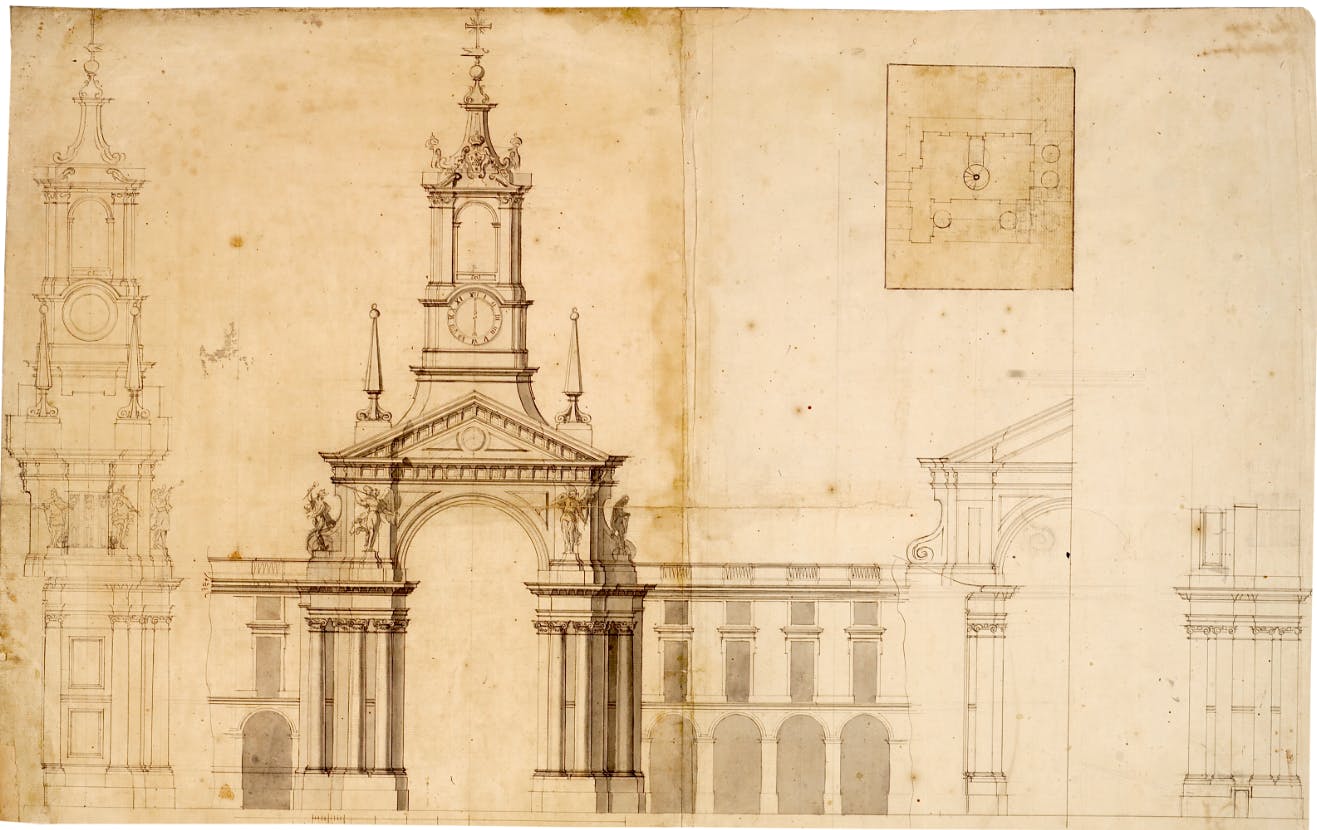

Welcome to the Sala dos Contos! This original drawing by Carlos Mardel symbolises the gateway to the exciting world that was Lisbon after the cataclysm. In this room you will finally be able to complete the mission that Professor Luís entrusted to you, to recover the lost knowledge of the three documents: Inquérito, Providências and Lisbon Plan. Here you will meet people from all walks of life who, after the earthquake, worked hard to rebuild the city, both physically and emotionally, from the secretaries of state, to the architects, the many anonymous friars and nuns who looked after the survivors, the servants and slaves, the galley prisoners?

This design is also a symbol of how the reconstruction was carried out, a process that took tens, even hundreds of years, with back and forth. Perhaps because it is a prominent place in the most emblematic Pombaline square, the true "city gate", this arch had various projects following this one by Carlos Mardel, designed in 1756 - the Triumphal Arch that stands there today was only completed in 1873.