Right after the quake, many people fled to Terreiro do Paço and to the banks of the Tagus, on the way to the sea, where there were no buildings. The captains of the many ships, situated offshore, felt the violent movement of the waters. About 250 km offshore, the quake had displaced trillions of litres of water, creating a tsunami that would hit Lisbon at around 11.00 am. The Bugio Tower overlooking Lisbon from the mouth of the Tagus river, was one of the first buildings to suffer the effects of the tsunami. The tower was surrounded by the tsunami waters, stranding a garrison of soldiers in the tower. They fired several shots to signal for help and had to move up to the top of the tower to survive the mounting waters.

At that time, most of the testimonies mention the retreat of the sea, which gave onlookers a view of the river bed like they never had seen. Then came the swelling of the waters, with the wave entering the city and submerging many seafaring settlements. Testimonies tell of shattered anchors thrown to the surface and of broken moorings. Many sailors describe how the ships ran dry and then were back afloat again.

The mass of water rose and turned into a wave reaching about five metres high. No one was expecting another catastrophe, people were taken by surprise. There was nowhere to hide, nowhere to seek shelter. The waters entered streets and squares, sweeping away wood, stones, and everything the sea could find along the way.

One witness reports that the river, seen from the square, rose in a mass of water like a mountain. The captain of a ship, some 300 meters from the shore, said he measured the rise of the river at about 6 meters. Several waves followed, in a flux and reflux of water that caused panic in the lower part of the city. The waves destroyed everything in their path, dragging people away and crushing boats and piers against buildings.

According to a witness, there was nothing left at Arsenal or Ribeira and the wood that was not washed away by the sea was clogged up in the streets, making the city impassable.

The Cais da Pedra, a fabulous and gigantic construction, situated between the quay of Terreiro do Paço and the fortification on the eastern part of the square, disappeared, probably sunk in the unstable mud, with the multitude of people who had taken refuge on this quay made of marble, thinking they were safe there. Countless boats full of people, who had sought an escape from the instability of the land, took to the river but were also swallowed by the oscillation of the sea. Many boats were dragged to the other bank of the River Tagus.

Despite the immediate escape of those who were on the banks and in Terreiro do Paço, many were carried away by the force of the water and those who resisted were left with water around their waists at a good distance from the shore, near S. Paulo.

The tsunami destroyed many of the already fragile buildings and killed many of the earthquake survivors. It is impossible to say exactly how many died from the tsunami, but estimations are at about 900 victims from a wave penetration of about 250 metres.

As the water receded and the extent of the damage became visible, the fires continued to rage, now fed by the tons of debris left behind by the tsunami.

Specialists do not yet agree on which fault or set of faults caused the 1755 earthquake. If it were just a single fault, that fault must have been enormous, at least 100 km long and 50 km wide. It may also have been two or more large faults rupturing in sequence. Historical information on the tsunami suggests that such faults must have been, when combined, 200 km in length and 80 km wide.

These faults are said to have affected the ocean floor, causing it to rise an estimated 20 m in height, and thus causing a transoceanic tsunami. The biggest impact was in Portugal and Morocco, also affecting southern Spain. In the case of mainland Portugal, the tsunami waves are estimated to have reached 10 to 15 m in the Sagres area and in Lisbon they are estimated to have reached 5 m in height. The different heights that were observed in distant points of the globe, but also in more contiguous regions, are justified by the speed at which the waves of a tsunami travel and by the characteristics of the ground in each area. The estimated time of arrival at the Bugio lighthouse, off Paço d'Arcos, is 30 minutes after the earthquake. In the case of Lisbon, as the water depth offshore is much shallower, the waves propagated much more slowly, thus taking an estimated 60 to 90 minutes to reach land.

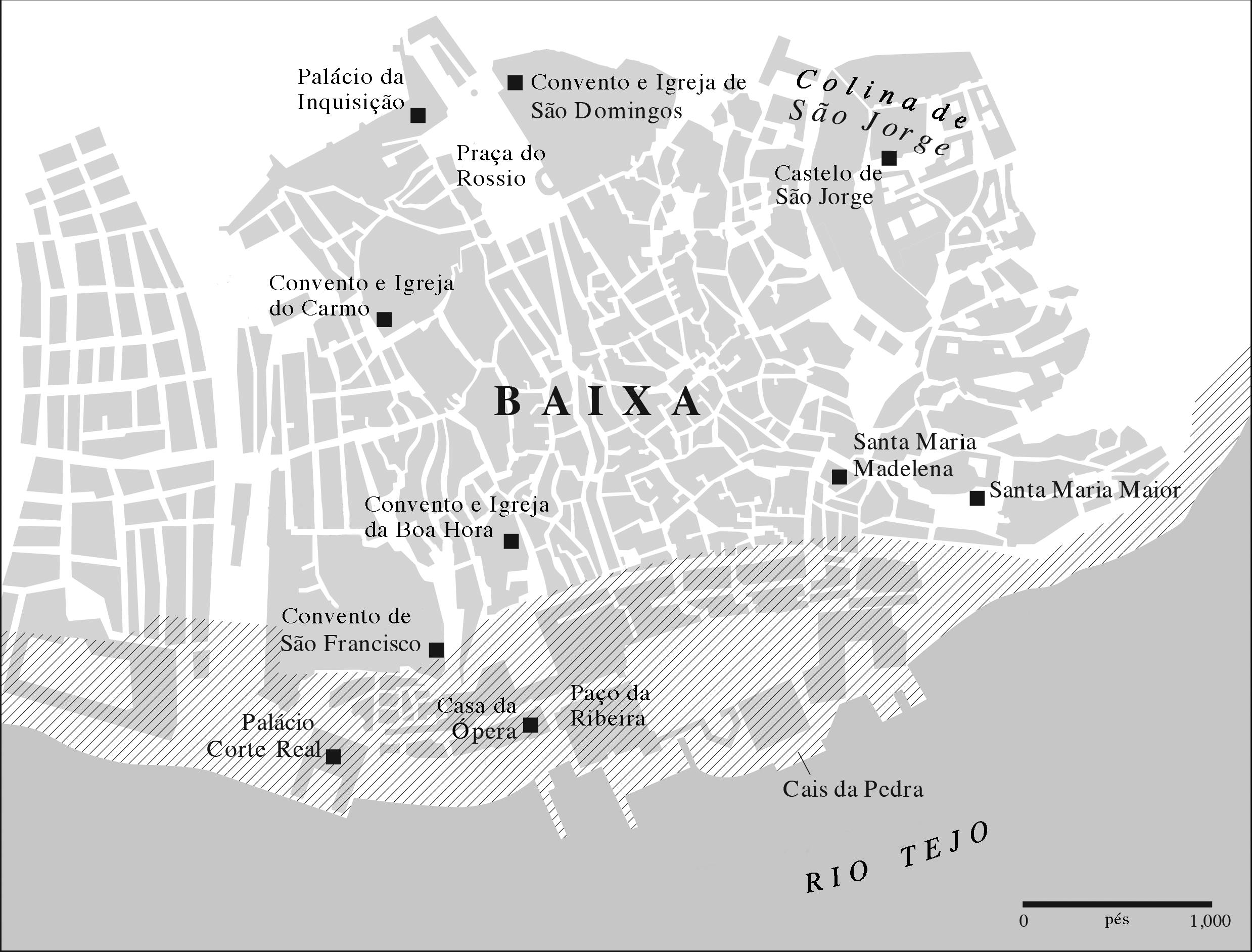

In this projection, we can see how the tsunami penetrated the lower city of Lisbon based on historical accounts. The water had advanced 250 to 350 meters around Terreiro do Paço, approximately up to the current location of the Rua Augusta Arch. Adding to the casualties, the flood caused catastrophic material damage, as most of the valuable goods arriving by sea were stored in warehouses and shipyards along the river.

Engraving represents the Lisbon earthquake, tsunami, and fire, where you can see the masterful representation of the royal palace’s large square tower collapsing. The horrors of the event travelled the world through letters, engravings, and gazette articles and stirred people’s imaginations for many years. Even 100 years later, we continued to see references to the earthquake, as seen with the poem “The Deacon's Masterpiece” by Sir Oliver Wendell Holmes, a verse text published in New York in 1857 that tells the story of a seemingly indestructible horse-drawn buggy made on the day of the earthquake:

“That was the year when Lisbon-town

Saw the earth open and gulp her down,”

Continue Exploring

Bibliography

Mark MOLESKY, This Gulf of Fire: The Great Lisbon Earthquake, or Apocalypse in the Age of Science and Reason, Vintage, 2015.

Russell R DYNES. «The Lisbon Earthquake in 1755: Contested Meanings in the First Modern Disaster», TsuInfo Alert, 2, no. 4, 2000, pp. 10–18.

Antonio dos REMÉDIOS, Resposta à Carta de Joze de Oliveira Trovam e Sousa, Oficina de Domingos Rodrigues, Lisboa, 1756.

Bento MORGANTI (José Acursio de Tavares), Carta de hum amigo para outro, em que se dá succinta noticia dos effeitosdo Terremoto, succedido em o Primeiro de Novembro de 1755. Com alguns principios Fisicos para se conhecer a origem, e causa natural de similhantes Phenómenos terrestres, Lisboa, Oficina de Domingos Rodrigues, 1756.

José Joaquim Moreira de MENDONÇA, Historia Universal dos Terramotos, Que tem havido no mundo, de que ha noticia, desde a sua creaçaõ até o seculo presente. Com huma narraçam individual Do Terremoto do primeiro de Novembro de 1755, e noticia verdadeira dos seus effeitos em Lisboa, todo Portugal, Algarves, e mais partes da Europa, Africa, e América, aonde se estendeu, António Vicente da Silva, Lisboa, 1758.

Historia universal dos terremotos, que tem havido no mundo, de que ha noticia, desde a sua creaçaõ até o seculo presente. : Com huma narraçam individual do terremoto do primeiro de novembro de 1755., e noticia verdadeira dos seus effeitos em Lisboa, todo Portugal, Algarves, e mais partes da Europa, Africa, e América, aonde se estendeu: e huma dissertaçaõ phisica sobre as causas geraes dos terremotos, seus effeitos, differenças, e prognosticos; e as particulares do ultimo. : Mendonça, Joachim José Moreira de : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Miguel Tibério PEDEGACHE (Ivo Brandão), Nova e fiel relação do terremoto que experimentou Lisboa, e todo Portugal No 1. de Novembro de 1755. Com algumas Observaçoens Curiosas, e a explicação das suas causas, Oficina de Manoel Soares, Lisboa, 1756 (1756) M. T. Pedegache – Nova e fiel relação do terremoto que experimentou Lisboa | Éditions Ismael (editions-ismael.com)

José de Oliveira Trovão e Sousa, Carta em que hum amigo dá notícia a outro do lamentável sucesso de Lisboa, sem local nem data de edição mas dada como escrita em 20 de Dezembro de 1755, Coimbra, 1755 Biblioteca Brasiliana Guita e José Mindlin: Carta em que hum amigo da noticia a outro do lamentavel sucesso de Lisboa (usp.br)

Rui TAVARES, O Pequeno Livro do Grande Terramoto, Tinta da China, 2009.