Share

Lisbon was a city of contrasts. The city was filled with the wealthy and the poor, living side by side. Hundreds of beggars roamed the filthy streets and waited in front of the monasteries and convents for food and shelter. Poor people depended on charity in 18th century Portugal and were mainly assisted by the Catholic Church. In addition, many wealthy aristocrats had “their” poor to whom they gave regular donations and assistance. Merchants and sailors of all ranks mingled in the streets with the many African women selling corn, rice, and cooked bacon.

A large number of craftsmen could get rich from professions that are considered modest today: Pastry chefs, confectioners, blacksmiths, and bakers. The biggest contracts were associated with luxury goods, goldsmiths, hairdressers, and tailors who could become very rich and influential, depending on their clientele. There were also important merchants in food, bread, meat, and wine which generated conflicts within the Lisbon Chamber. On the other hand, trade apprentices could sometimes belong to very poor families and be placed—almost in semi-slavery—to learn the trade of shoemaker, barrelmaker, or ropemaker. A multitude of servants, aristocratic lords, captains, and even friars lived a life of dependence—sheltered in the master's house, if they were expelled from their work, they fell into poverty. The most unusual case was that of the soldiers. They earned their wages, sometimes just food, especially during wartime. They lived on very little, receiving their wages late and sometimes going unpaid for months and even years. There were reports of soldiers, sometimes even officers, with ragged and miserable shoes. Crime and begging increased and became one of Lisbon’s trademarks in the mid-18th century, and the subject was heavily discussed by the authorities.

There was also a multitude of people linked to unskilled work and sea trades—from fishermen's assistants, oarsmen, sailors, and porters, to sellers of fried fish and sardinellas—living from day to day.

Many of these jobs were carried out by enslaved people, inhabiting the most unprotected part of society. They were also rented by their masters for daily work, although some earned money as artists, singers, guitar players, or whitewashers. Even after they were freed, many enslaved people continued to do these jobs.

With around 200 000 inhabitants, Lisbon was the 4th largest city in Europe and although travellers considered it filthy, full of stray dogs and large animals, the wealth of the palaces and churches impressed foreigners: Gold ciboriums of the Patriarchal Church, safes of the House of India, jewels of the Church of Saint Roque, and the interior of the churches, where diamonds glittered on curtains, tablecloths, and vestments, and altars were covered in gold. The most extreme example was the famous Patriarchal Church, with its legion of musicians and singers. The cardinal patriarch drove around the streets in a coach with his dozens of servants, wearing wide shorts, wigs, and red robes embroidered in gold, imitating the Pope's retinue. Palace walls contained the rarest of treasures, like the Duke of Lafões' house, where there were paintings by Titian, Veronese, and Rubens. In these palaces, food was served in magnificent silver plates during sumptuous parties. Rich women dressed in French fashion, with oriental shawls wrapped around their shoulders. In Paço da Ribeira, home of the King, tapestries from Flanders lined the walls, ceilings were painted by Italian masters, and Chinese porcelains were everywhere. There was also a vast library with some 70,000 volumes and all the rare and precious objects accumulated by centuries of diplomatic gifts.

A painting with several interesting details: A funeral procession, something unusual to see represented in the Rossio square, and a man hanging by the arms from a post. Suspended, not hanged, is more like a punishment or public humiliation. This scene reminds us that the Inquisition had its seat here, with its court and prison, and that it was also here that the “autos-de-fé” were carried out. At the back, the rich detail in the Manueline façade of the Hospital de Todos os Santos.

On this panel of Baroque azulejos, we can see the market of Ribeira Velha in Lisbon. Before the earthquake, the people of Lisbon used to come to buy their fish, fruit, and vegetables. Notice how far the river waters reached, with boats moored and fishermen carrying baskets. Notice women selling and a more distinguished figure, perhaps a wealthy merchant. Among the surrounding houses, almost all of which have porches and shops, take a look at the particular façade of the Casa dos Bicos.

Continue Exploring

Bibliography

Maria Isabel Braga ABECASIS, A Real Barraca, A Residência na Ajuda dos Reis de Portugal após o Terramoto (1756-1794), Tribuna da História, 2009.

Laurinda ABREU, O poder e os pobres, as dinâmicas politicas e sociais da pobreza e da assistência em Portugal (séculos XVI-XVIII), Gradiva, 2014.

Mário Reis de CARMONA, O Hospital de Todos os Santos da Cidade de Lisboa, edição do autor, 1954.

Arthur LAMAS, A Quinta de Diogo de Mendonça no Sítio da Junqueira, Lisboa, 1924

Maria Antónia LOPES, Mulheres, espaços e sociabilidade: a transformação dos papéis femininos em Portugal à luz de fontes literárias (segunda metade do século XVIII), Livros Horizonte, 1989.

Vitorino Magalhães GODINHO, Estrutura da Antiga Sociedade Portuguesa, Edições Setenta, 2019.

Nuno Luís MADUREIRA, Lisboa Luxo e Distinção 1750-1830, Fragmentos, 1990.

Fernanda OLIVAL, As ordens militares e o Estado Moderno: Honra, Mercê e Venalidade em Portugal (1641-1789), Star, 2001.

Mary del PRIORE, O Mal sobre a Terra, História do Grande Terramoto de Lisboa, Objectiva, 2020.

Nuno SALDANHA, Joanni V Magnifico, A Pintura em Portugal ao tempo de D. João V, Catálogo da Exposição, IPPAR, 1994

Piedade Braga SANTOS, Teresa RODRIGUES e Margarida Sá NOGUEIRA, Lisboa Setecentista vista por estrangeiros, Livros Horizonte, 1987.

Maria Beatriz Nizza da SILVA, Ser nobre na colónia, Editora UNESP, 2005

Rui TAVARES, O Pequeno Livro do Grande Terramoto, Tinta-da-China, 2010.

Show other RFID points

Lisbon 1755 - A city of contrasts

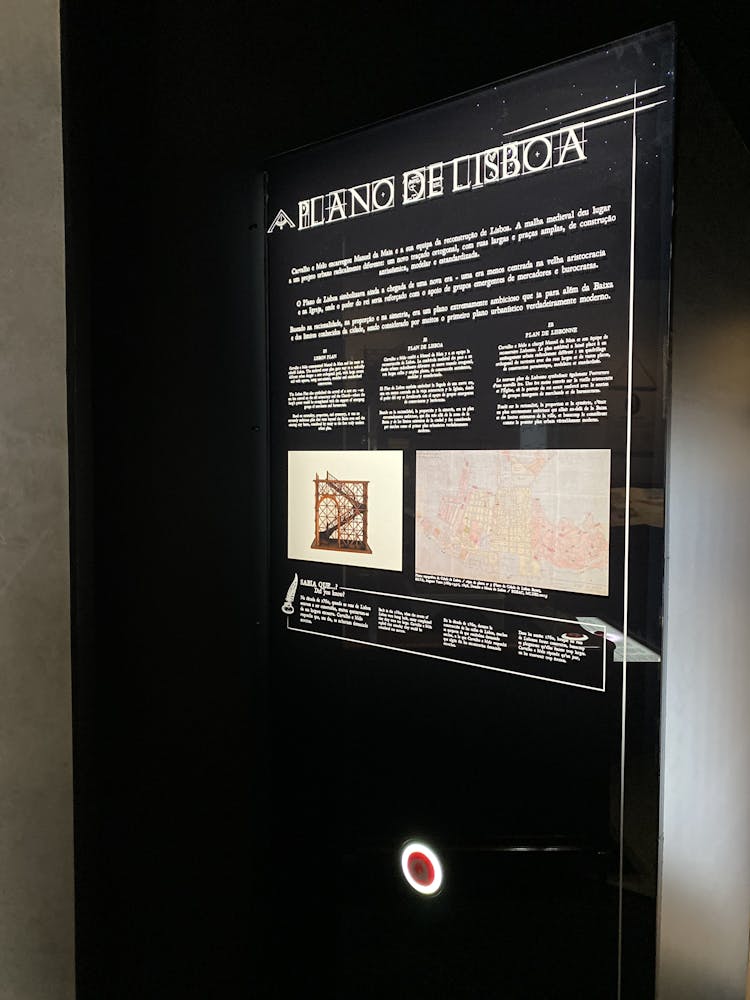

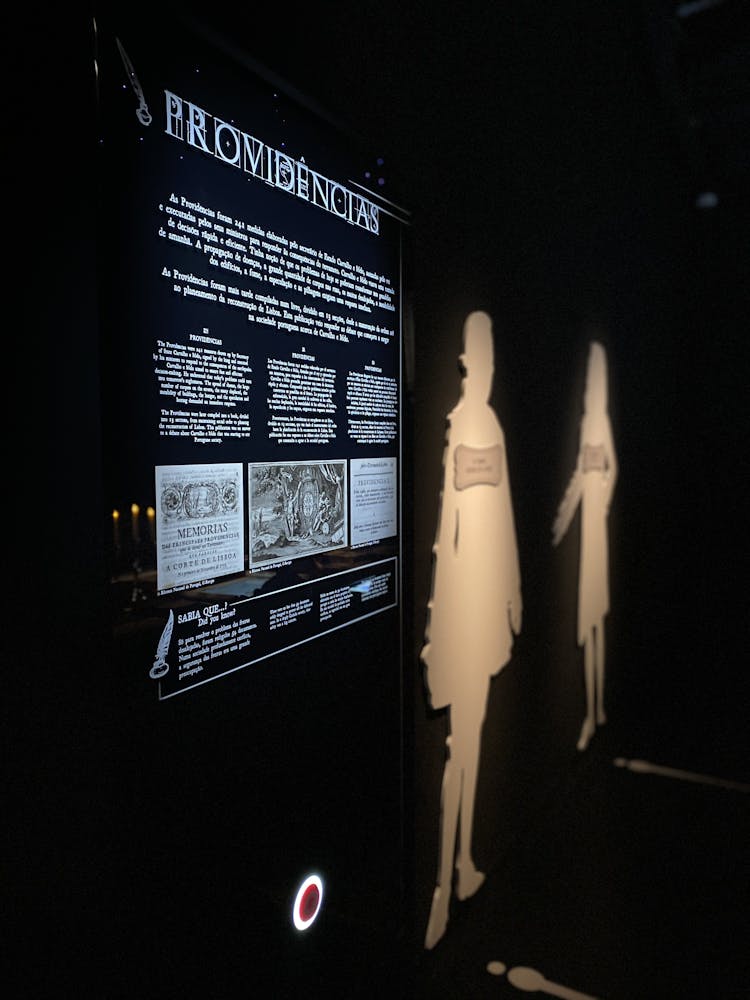

Providências

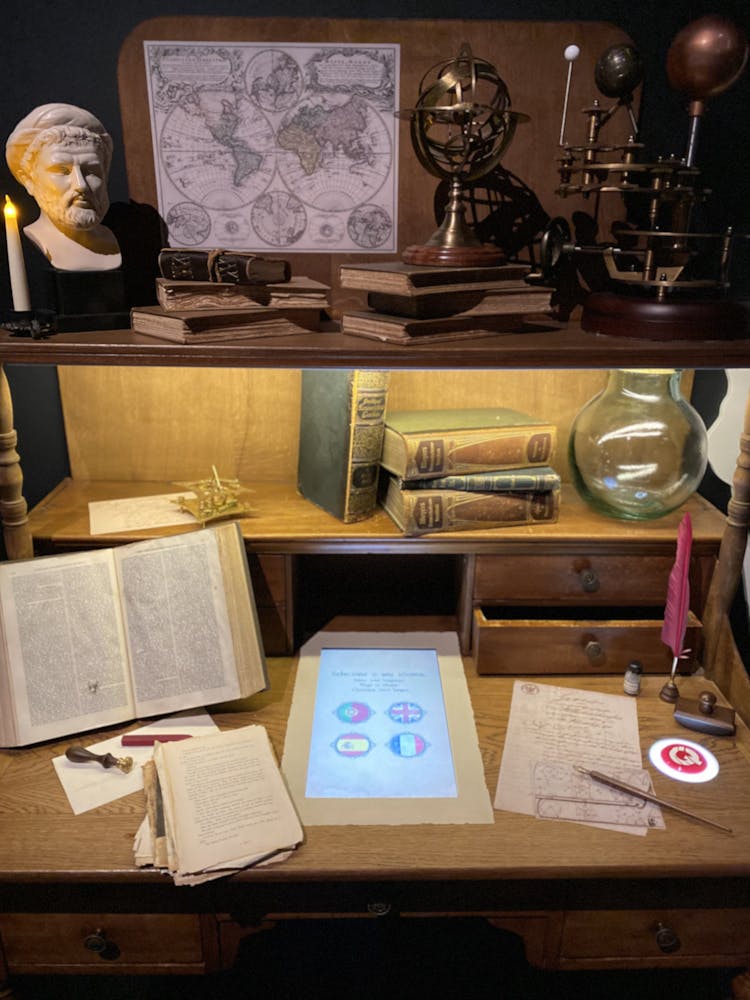

The German merchant

Surgeon Bleeding Barber

The people in the streets

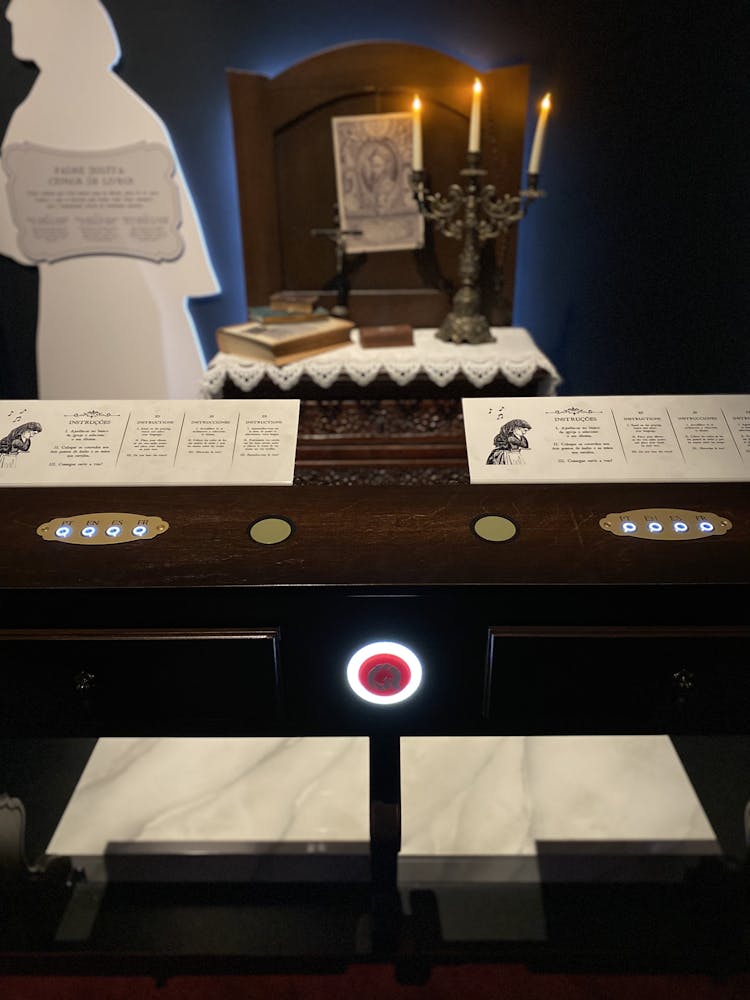

Jesuit book censor Priest

Carpenter accused of bigamy

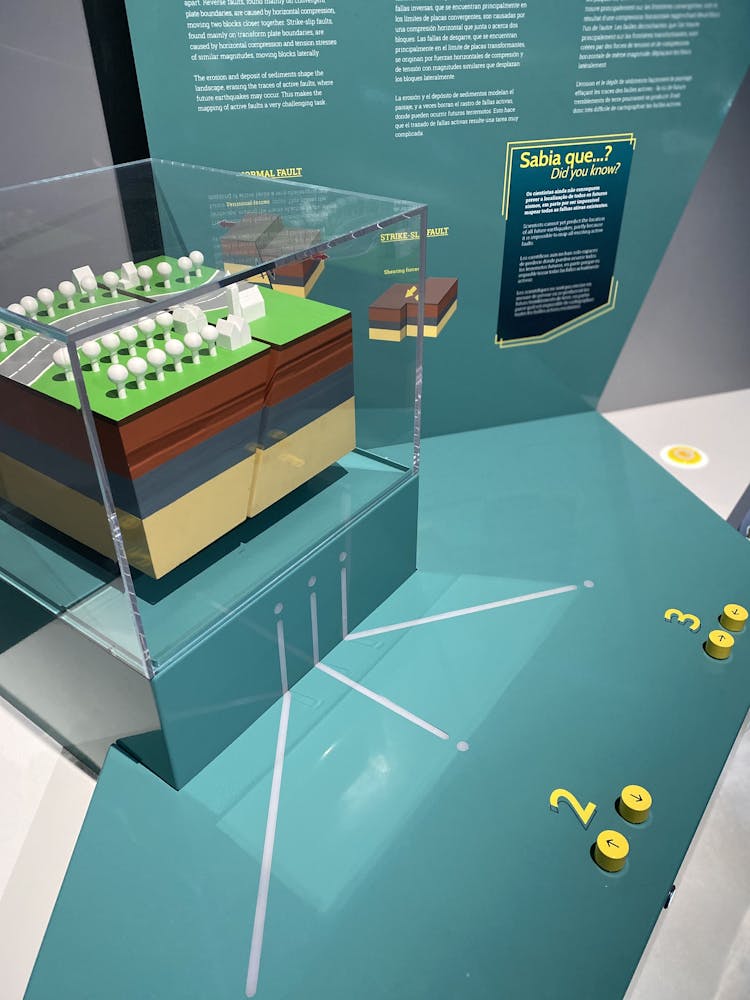

Tectonic Plates and Moving Plates

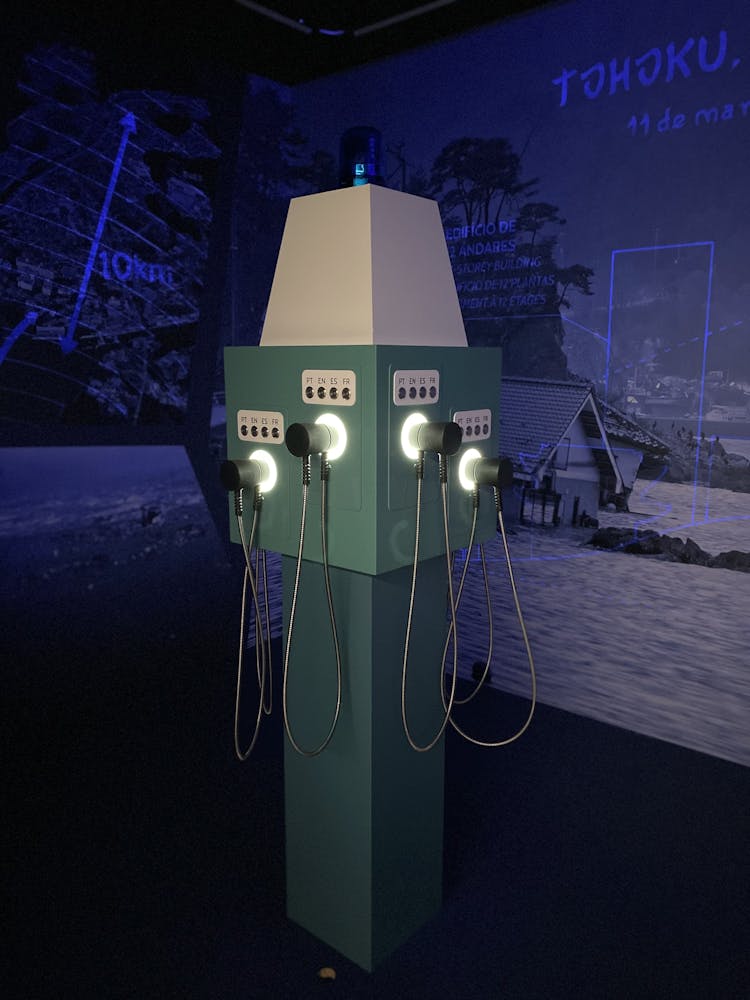

San Francisco and Tohoku

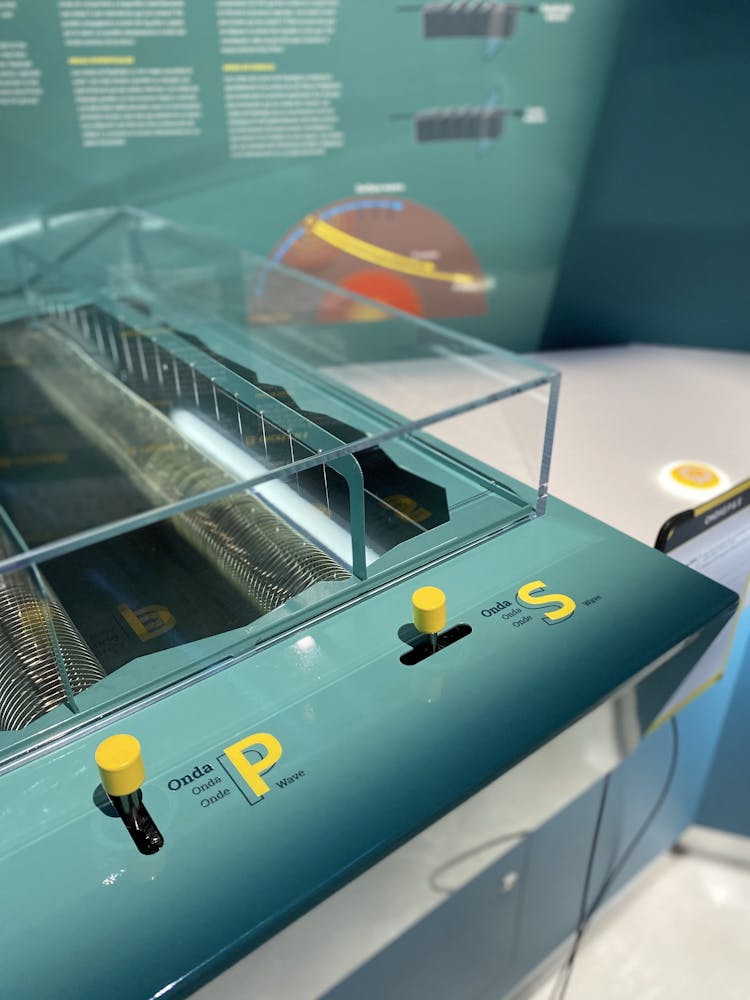

P&S Waves

The Size of an Earthquake

Are we prepared for the next one?

Anti Seismic Constructions

African enslaved woman bought in Lisbon

Continental Drift

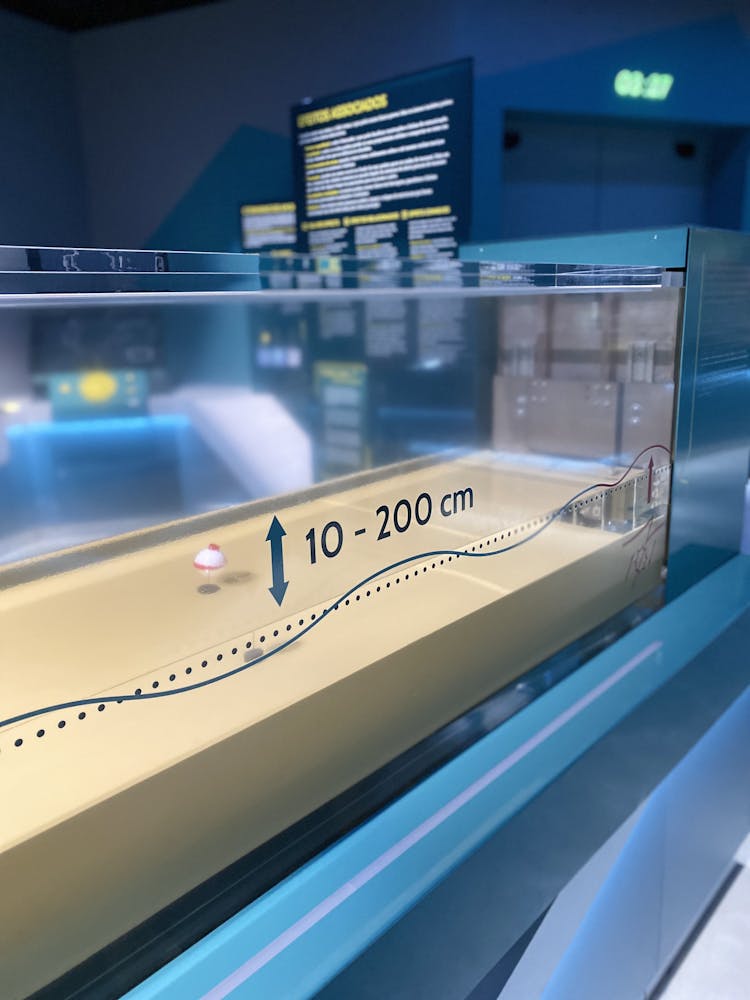

The Tsunami

Seismometer

Richness of the city and gold smuggling

Portugal Tectonics and Lisbon Quakes

How the fires started and propagated

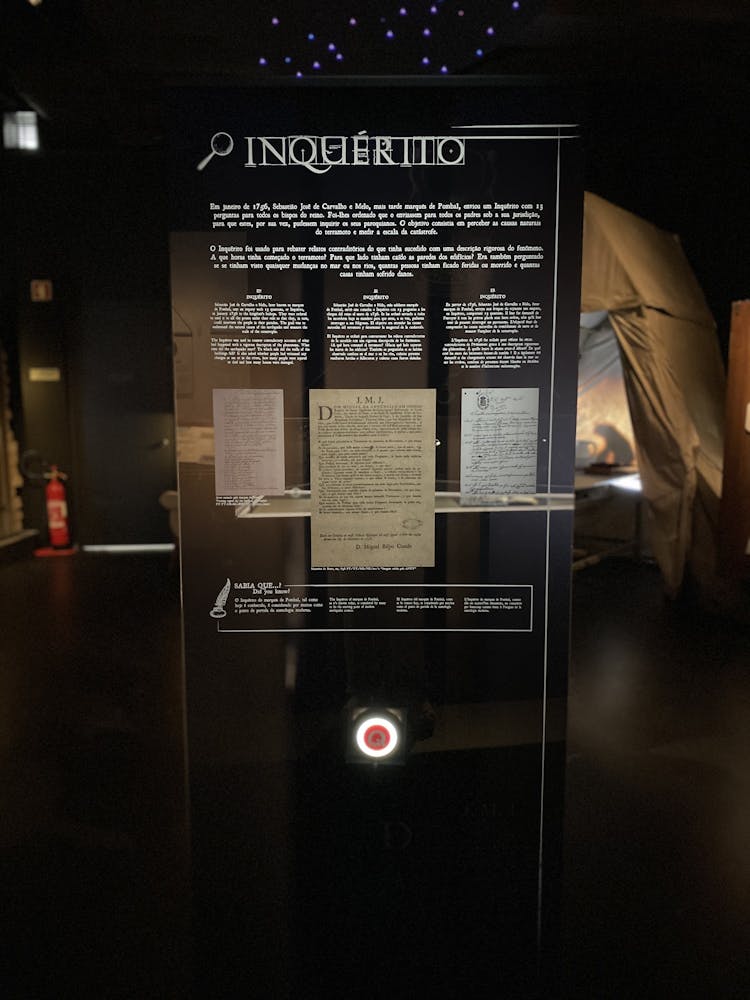

Inquérito

The losses

The three missing documents

Traditional Rite Masses

The connection with the colonized territories

What happened right after the quakes

Presence of the Catholic Church

Related Effects

The King's Ministers

Earthquakes and Faults