Share

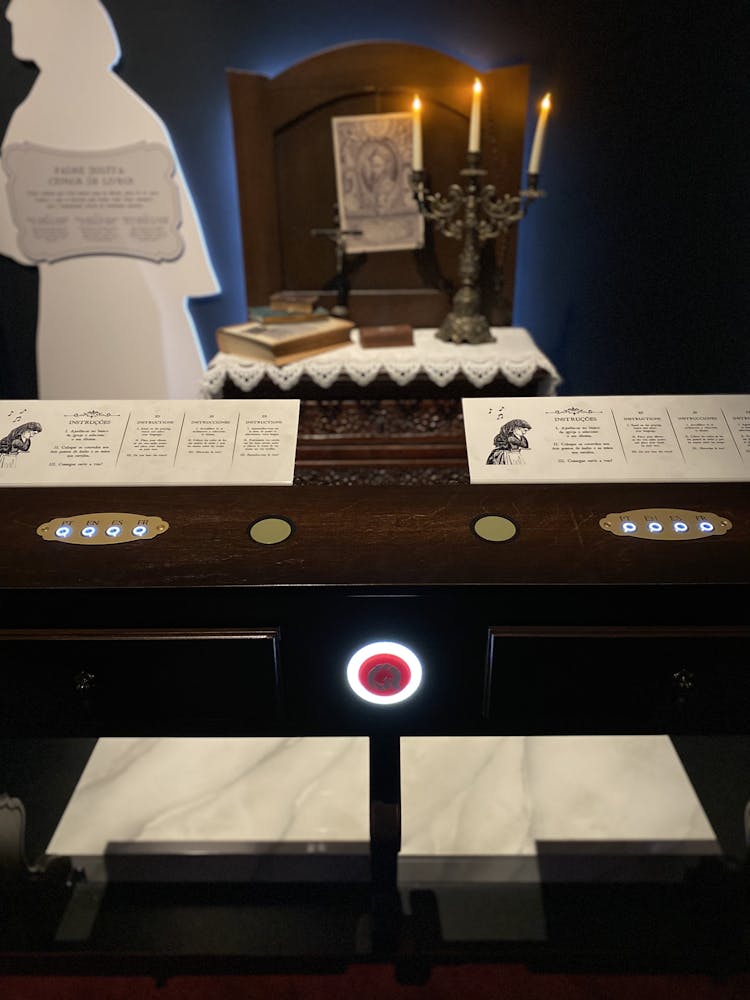

The earthquake happened on the 1st of November, on All Saints Day, an important feast day in the liturgical calendar. Lisbon, one of the most fervently Catholic cities of the 18th century, was in effervescence that day. Its churches were decked out and filled with the faithful attending mass when the earthquake struck at 9.40 a.m. Three tremors in the space of nine terrifying minutes hit the city.

Despite the unreliability of testimonies recorded under the traumatic effect of the experience, and some later transcribed by indirect witnesses, a description of the chronology of the Earthquake can be estimated. At first, a bang was heard, a kind of thunder, and then the first tremor, lasting slightly more than a minute. Many witnesses speak of a sensation similar to riding giant chariots or thousands of galloping horses. Other witnesses compared the rumble to a herd of elephants. After a short interval, not over a minute, they felt the second tremor, with greater violence. It lasted about two minutes and the first houses began to fall. The roofs and “sobrados” (wooden floors) collapsed and the plaster bounced off the walls. Walls opened up and towers fell. The third quake followed and this is when testimonies are more diffuse. Almost all claim that most of the damaged houses collapsed at this stage. Many say they saw the earth and the city rippling, like a cornfield shaken by the wind. Others refer to the tiles blown away like feathers. The collapsed buildings cast a suffocating cloud of dust over the city, darkening the streets and blocking out the sunlight. Most witnesses speak of a total duration of 6 to 9 minutes. Some mention only two tremors, not distinguishing the second from the third.

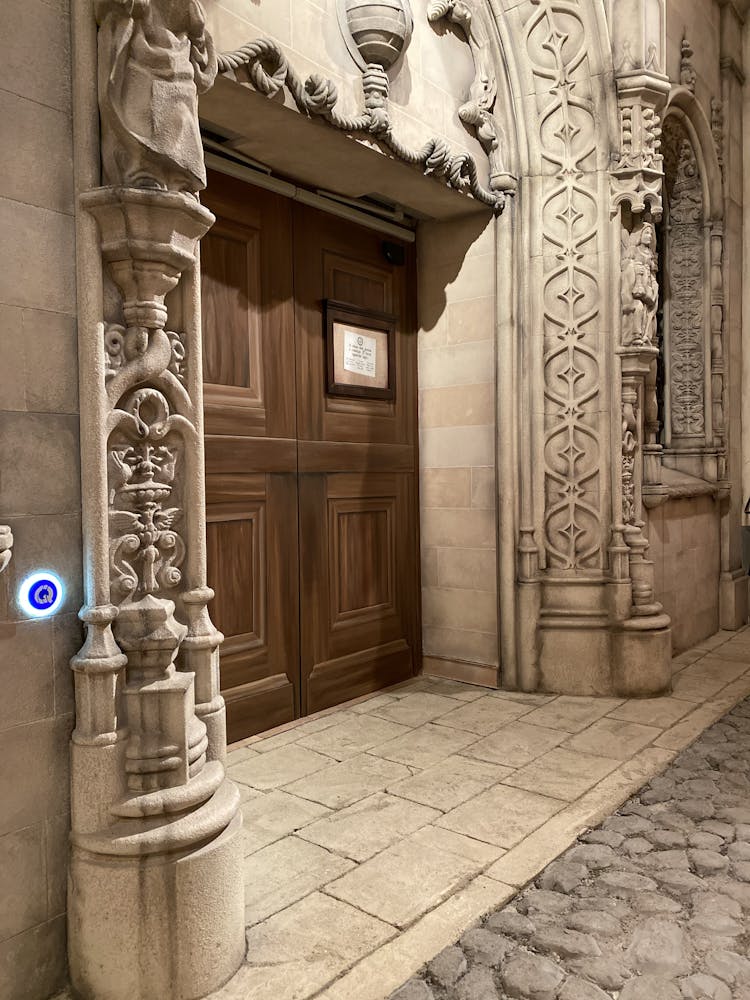

The churches were full at the time of the tremors and many died with the collapse of the stone vaults, as was the case in the Church of Carmo. Many of the aristocrats survived the disaster, as they usually attended mass after eleven o'clock in the morning, and many of them were outside the city, in palaces or country houses.

The fires started soon after in many places at once, spreading mainly from the Rossio area. The falling candles and chandeliers brought out to celebrate All Saints’ Day set fire to furniture, wooden objects, and fabrics in churches and chapels. As it was a day of celebration, the ovens in houses and bakeries were also working at full capacity at that time of the morning, preparing the delicacies that would be eaten that day by the Lisboetas and the many visitors that were in the city. They quickly caught fire and the fire spread from the kitchens to the rest of the houses. Fires inside buildings soon spread to neighbouring structures because of the strong winds.

The horror of the fire was compounded by the many injured trapped in the earthquake rubble or disabled in beds, caught in the flames. The fire was so devastating and deep that more than a month later, buildings and rubble were still burning. António dos Remédios, an eyewitness, published a letter refuting some of the more exaggerated testimonies, but underlined the horror of the fire, with the many people burnt alive.

The structures of houses in pre-earthquake Lisbon were made of wood, as were many of their walls and floors. Many buildings had overhanging floors, with upper floors advancing over the street. This extra floor space was great from the inside, but out in the street, each floor became more dangerously close to the opposite building. This structure created genuine tunnels in the already narrow, serpentine streets of downtown Lisbon, through which the strong wind, heated by the fire, advanced like a furnace that day. On some of the streets that day, you could only survive for less than a minute before the thick smoke killed you.

To make matters worse, Lisbon had a very poor water supply at the time. Brawls between watermen and water shortages were common in the capital. The Águas Livres Aqueduct, built during the previous reign, would provide some response to this calamity, but in 1755 there were still very few public fountains. On the day of the earthquake, many of these infrastructures were destroyed.

Even the waves of water caused by the tsunami didn’t put the fires out. Instead, they carried even more debris that fed the surrounding fires. To make matters worse, thieves also set fire to buildings to scare people away from their possessions. Desperate, the survivors abandoned their homes and fled to the suburbs. Without water or arms to put it out, the fire could spread at will, devouring everything in its path.

The wind continued to blow and the fires burned for days, prolonging the feeling that God’s wrath had hit Lisbon and the Final Judgement had arrived. The four elements—Earth, Water, Air, and Fire—seemed to have gathered their forces against the people. But fire was undoubtedly the most destructive element, causing much more damage than the earthquake or the tsunami.

Replicas of the earthquake were felt throughout the day, several times, but much lighter. In the early morning of November 8, 1755 there was another aftershock, quite violent, collapsing some already damaged buildings and aggravating the climate of panic. On the twenty-fifth of December, at two o'clock in the morning, the earth shook slightly for the last time in the year 1755, in Lisbon.

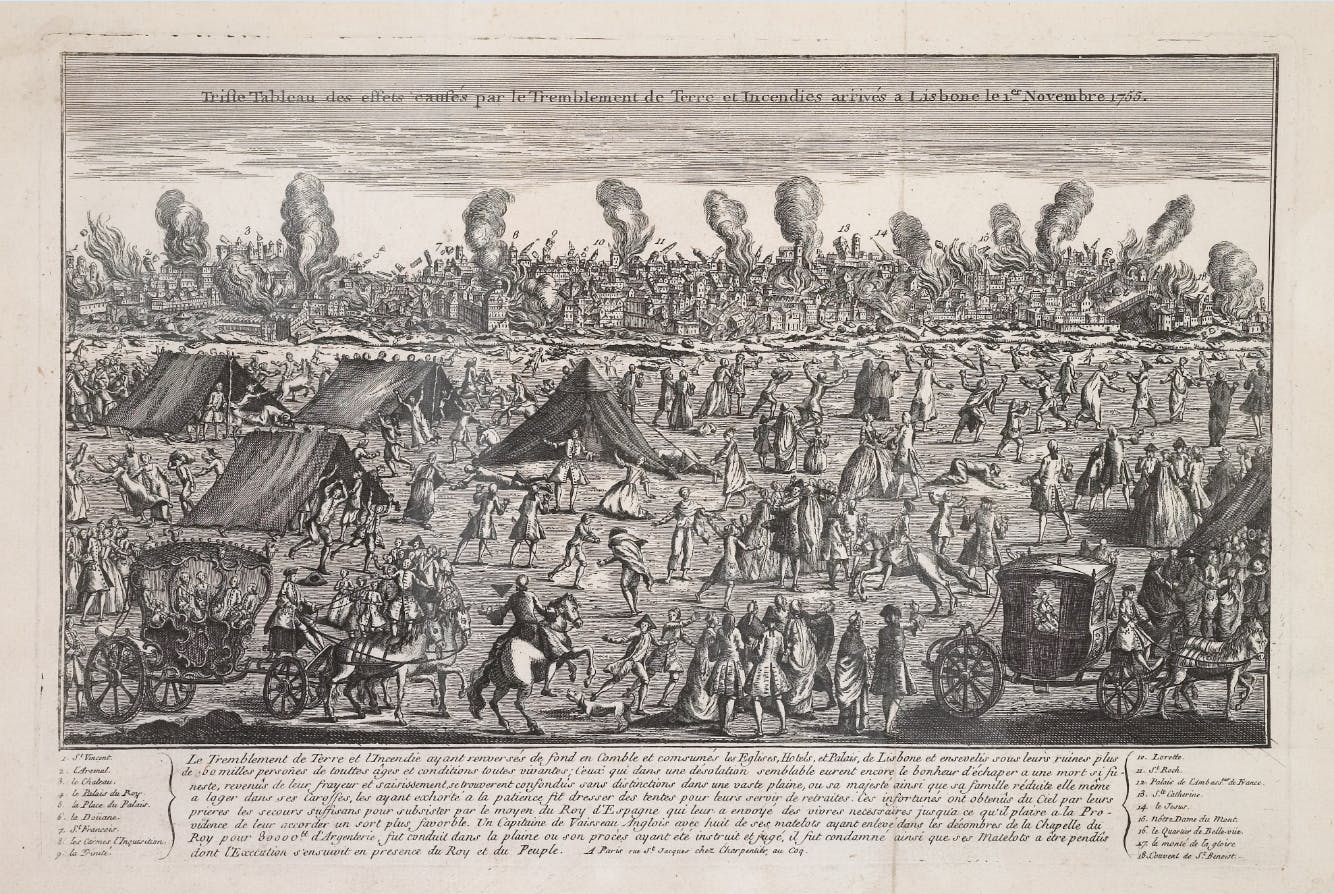

This French engraving shows the fires still raging on the horizon while survivors begin to take shelter in tents in the foreground. It is also possible that the artist tried to represent all the horrors of the event in one single image: The earthquake, tsunami, and fires. In the distance, church towers can be seen collapsing while the river’s raging waters are rising and fires are raging in every corner of the city.

Bibliography

Adélia Maria Caldas CARREIRA, Lisboa de 1731 a 1833: Da Desordem à Ordem no Espaço Urbano Lisboeta, Tese de Doutoramento em História de Arte, FCSH, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2012.

José Joaquim Moreira de MENDONÇA, Historia Universal dos Terramotos, Que tem havido no mundo, de que ha noticia, desde a sua creaçaõ até o seculo presente. Com huma narraçam individual Do Terremoto do primeiro de Novembro de 1755, e noticia verdadeira dos seus effeitos em Lisboa, todo Portugal, Algarves, e mais partes da Europa, Africa, e América, aonde se estendeu, António Vicente da Silva, Lisboa, 1758.

Miguel Tibério PEDEGACHE (Ivo Brandão), Nova e fiel relação do terremoto que experimentou Lisboa, e todo Portugal No 1. de Novembro de 1755. Com algumas Observaçoens Curiosas, e a explicação das suas causas, Oficina de Manoel Soares, Lisboa, 1756 (1756) M. T. Pedegache – Nova e fiel relação do terremoto que experimentou Lisboa | Éditions Ismael (editions-ismael.com)

António Pereira de FIGUEIREDO, Comentário latino e portuguez sobre o terremoto e incêndio de Lisboa, Lisboa, 1756. Versão em inglês A narrative of the earthquake and fire of Lisbon by Antony Pereria, of the Congregation of the Oratory, an eye-witness thereof, Printed for G. Hawkins, 1756.

Correspondência do Núncio Filippo Acciaiuoli, O terrível terramoto da cidade que foi Lisboa, Arnaldo Pinto Cardoso, Aletheia. 2013.

José de Oliveira Trovão e SOUSA, Carta em que hum amigo dá notícia a outro do lamentável sucesso de Lisboa, sem local nem data de edição mas dada como escrita em 20 de Dezembro de 1755, Coimbra, 1755 Biblioteca Brasiliana Guita e José Mindlin: Carta em que hum amigo da noticia a outro do lamentavel sucesso de Lisboa (usp.br)

José Acúrsio de TAVARES, Verdade Vindicada ou resposta a huma carta escrita em Coimbra, em que se dá noticia do lamentável sucesso de Lisboa, no dia I de Novembro de 1755, Officina de Miguel Manescal da Costa, Lisboa, 1756.

Mark MOLESKY, This Gulf of Fire: The Great Lisbon Earthquake, or Apocalypse in the Age of Science and Reason, Vintage, 2015.

Rui TAVARES, O Pequeno Livro do Grande Terramoto, Tinta da China, 2009.

O grande terramoto de Lisboa, 1755, 4 volumes, Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento-Público, 2005.

João Duarte FONSECA, 1755, O Terramoto de Lisboa, Argumentum, 2005.

Show other RFID points

Lisbon 1755 - A city of contrasts

Providências

The German merchant

Surgeon Bleeding Barber

The people in the streets

Jesuit book censor Priest

Carpenter accused of bigamy

Tectonic Plates and Moving Plates

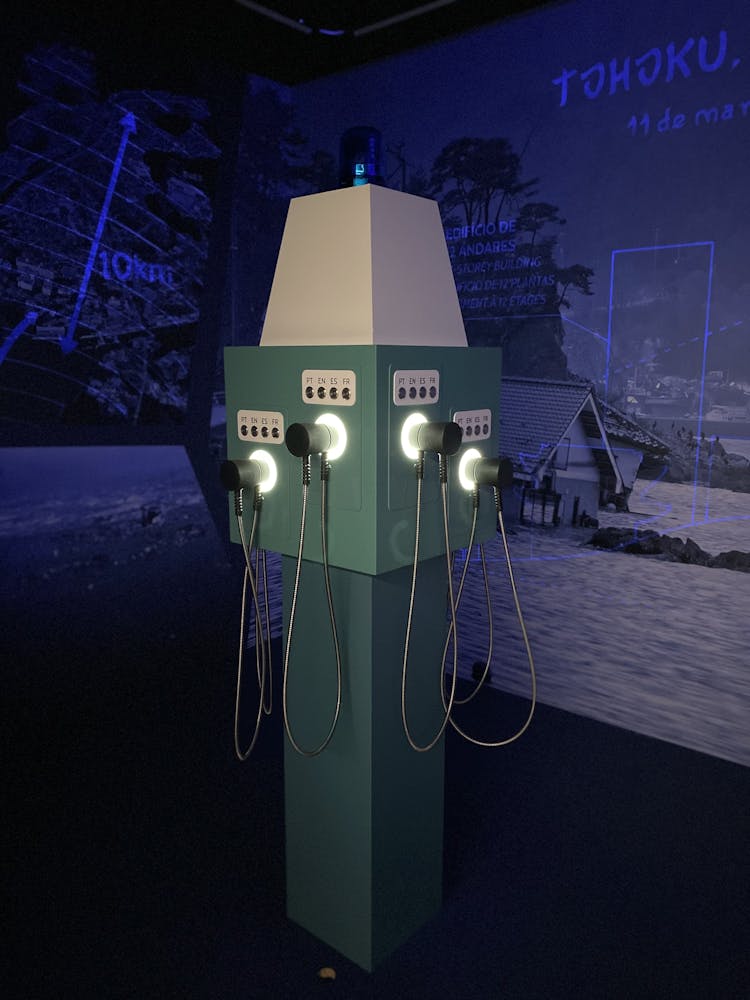

San Francisco and Tohoku

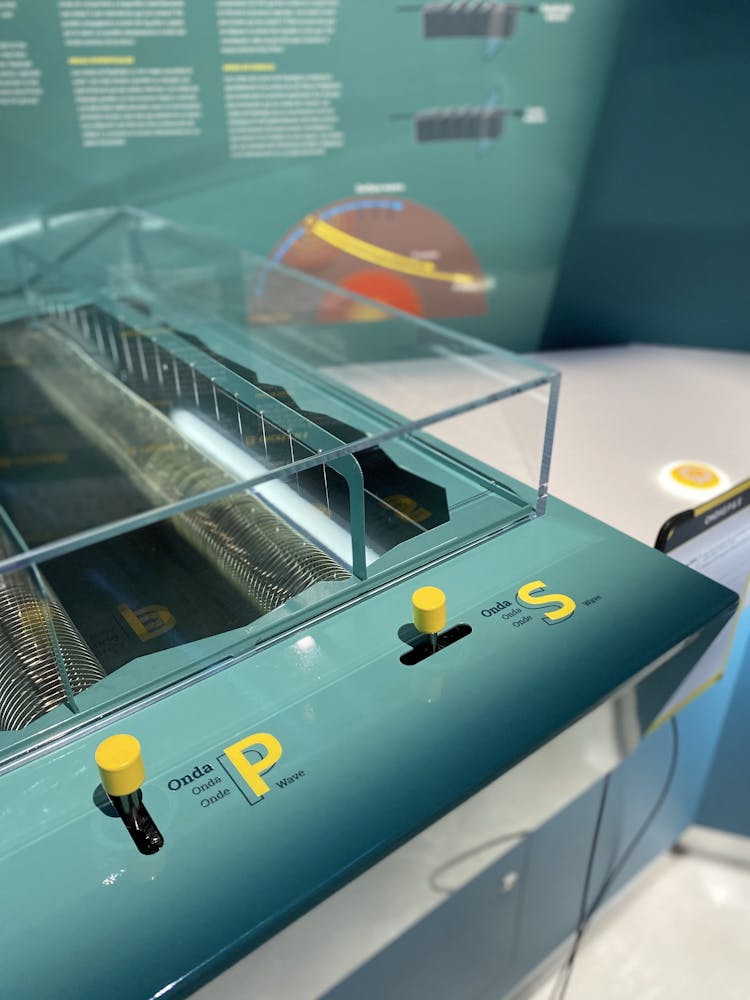

P&S Waves

The Size of an Earthquake

Are we prepared for the next one?

Anti Seismic Constructions

African enslaved woman bought in Lisbon

Continental Drift

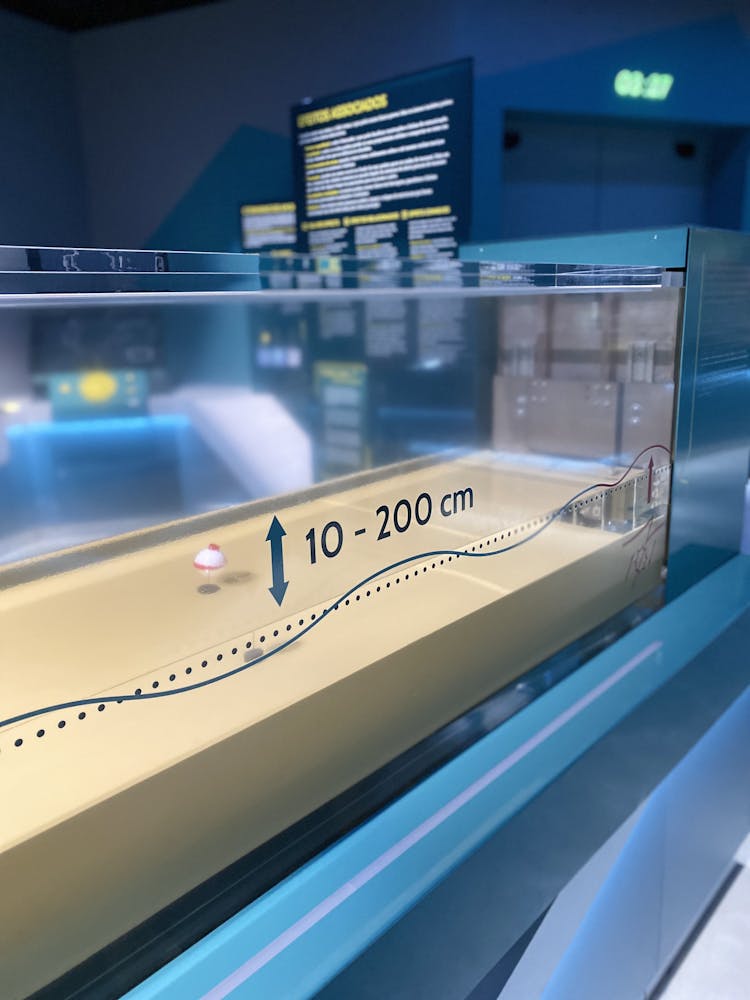

The Tsunami

Seismometer

Richness of the city and gold smuggling

Portugal Tectonics and Lisbon Quakes

How the fires started and propagated

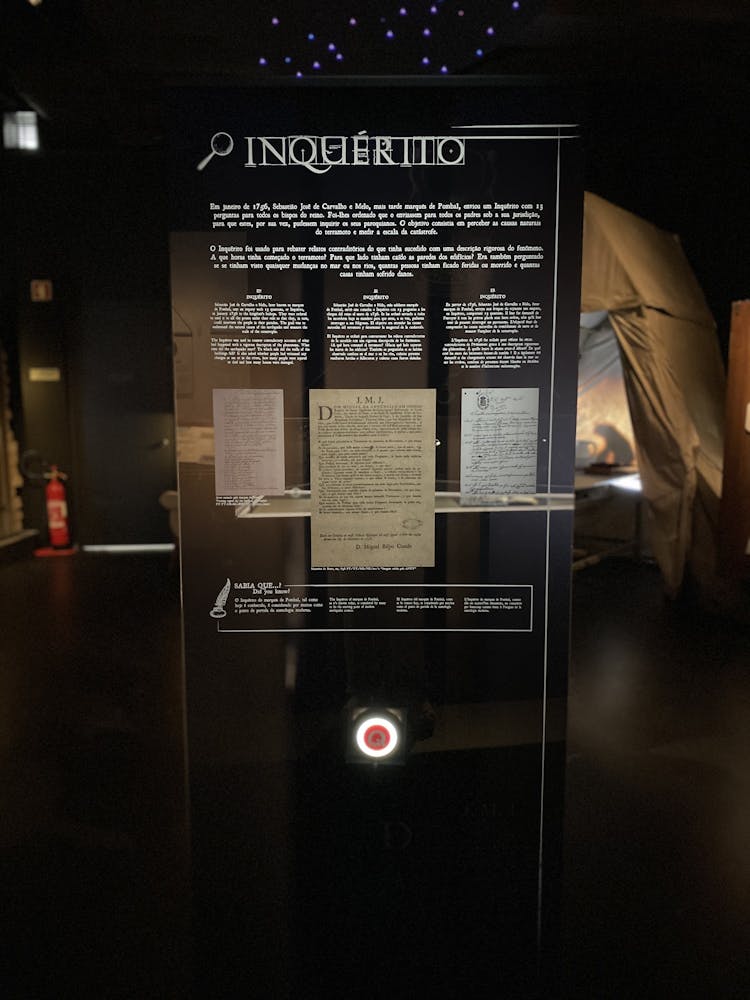

Inquérito

The losses

The three missing documents

Traditional Rite Masses

The connection with the colonized territories

What happened right after the quakes

Presence of the Catholic Church

Related Effects

The King's Ministers

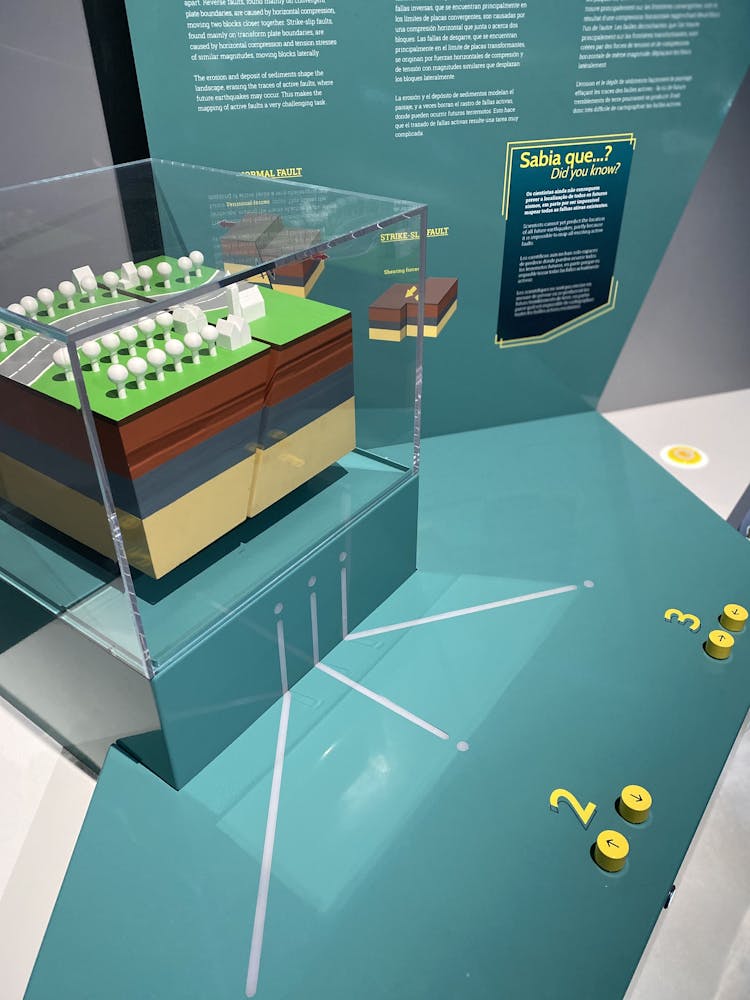

Earthquakes and Faults