Share

In the late 17th century, the discovery of gold deposits in Brazil led to a rush for this precious metal that would help in solving Portugal’s trade deficit, but in the long term it would aggravate the kingdom's relative poverty. It was a genuine “gold fever”: When mining started in the 18th century, nuggets weighing more than 2.7 kilos were extracted from streams. In a torrent of bars and coins, Brazil's gold arrived in Lisbon, allowing the purchase of French clothing, rich furniture from the East, and financing lavish feasts and parties with sumptuous fireworks, as well as the building of majestic monuments such as the famous Patriarchal Church, with its legion of musicians and singers, and the brand-new Tejo Opera House, where there were luxurious loges and even a door for horses to enter on stage.

Lisbon impressed foreigners and travellers with the amount of gold displayed on palaces, churches, and even on carriages. Shipments of gold mined in Brazil and carried by boats into Lisbon harbour were watched closely by the king’s troops—a warning to anyone who had plans to smuggle the precious metal.

However, a significant amount of gold was smuggled out of the country and sent to England, causing high diplomatic tension between both countries. Contrabandists like the infamous Fernando Wingfield and Duarte Roberts were always finding new and creative ways to bring the gold over. Their modus operandi was so brazen that it caused an international scandal. They were arrested, had their property seized, and faced a death sentence. Yet, both were pardoned, not banished, and had their goods returned to them.

It was somewhat normal to possess luxurious objects from India and China—porcelain, silk, and furniture made from precious woods. True luxury, however, was found in products from Europe, like French clothing and silverware, or the Italian and Dutch paintings that covered the walls of many palaces. Naturally, this easy consumption of products manufactured outside the kingdom would further weaken the Kingdom of Portugal’s already weak industry.

Sugar was another way to show wealth. There were so many wooden boxes of sugar stored at the Customs House that they had to find another place to store them. Finally, they chose the stables of one of the most important palaces in Lisbon, the Corte Real Palace, by the river. Corte Real Palace was one of about 50 palaces in the city that disappeared, either destroyed by the earthquake or seriously damaged by the fire.

Although Portuguese noblemen were not particularly wealthy compared to the nobility of northern Europe, Lisbon palaces were considered magnificent, built in “cantaria” (a kind of marble) and highly praised by travellers. They were richly furnished, assisted by numerous servants—in the case of the palaces of the dukes and marquises there were usually more than 50 people—with many carriages and even more horses. The richer ones had English mirrors decorated with silver, tapestries from Flanders, carpets from Persia and China, Japanese furniture, Chinese pots, Indian crockery, chairs cushioned with velvet, damask curtains with gold embroidery, oratories, and many Italian paintings.

The gardens, especially in the palaces on the edge of the city, could be impressive, authentic monastery enclosures, with woods, slabbed pavements, tiled panels, marble balconies, gardens with various decks, stone colonnades and even lakes with varied species of fish. Infamous parties were held in these gardens, using up to 8,000 lights and many fireworks.

After the earthquake, many of these superb palaces were not rebuilt, perhaps the only noteworthy absence that travellers would find in the newly rebuilt city. Among the most lamented palaces were those of the Counts of Ericeira, endowed with a vast library. Of the 80 or so palaces of noblemen and titled holders in Lisbon, almost two thirds disappeared.

When there was an official visit of great importance, the custom was to organise a procession on the Terreiro do Paco, with luxurious gifts such as ornate weapons, clothes, and money. This painting shows 12 carriages and litters carrying noblemen and dignitaries of the kingdom, for the first audience granted by Dom Pedro II to Monsignor Giorgio Cornaro, the representative of the Pope. The fourth carriage was the king's, sent to fetch the nuncio and driven by the Marquis of Alegrete.

This triumphal carriage was part of a group of coaches that were part of the procession of the Embassy to Pope Clement XI, sent to Rome by King João V in 1716. Filled with allegorical figures in gilded woodcarving, it represents one of the Portuguese maritime achievements: the discovery of the passage from the Atlantic Ocean to the Indian Ocean.

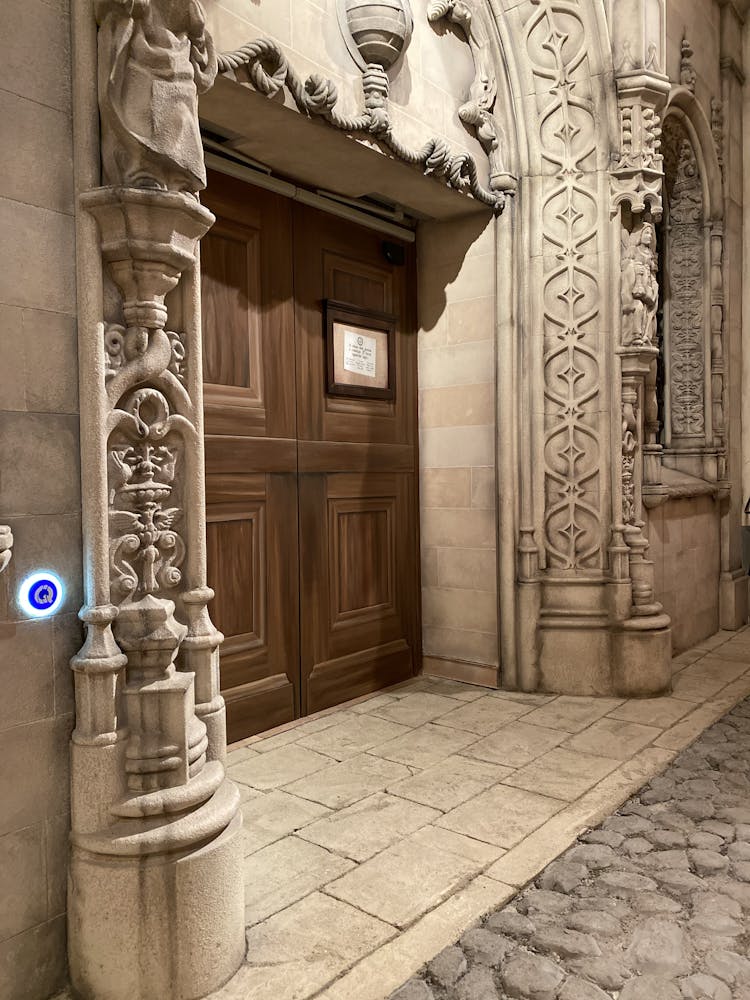

In 1747, the church of São Roque was honoured with the monument that King John V had designed and built in Italy: The Chapel of St. John the Baptist. The chapel was dismantled to be transported on three ships, but not without being blessed beforehand by the Pope, who had celebrated mass there. Its coating combines several marble and precious stones: Lapis lazuli, agate, antique green marble, alabaster, Carrara marble, amethyst, red porphyry, white and black marble from France, antique breccia, diaspore, jade, and others.

"The dobra was an artistic object. King Dom João V made himself represented on this coin as an absolute sovereign. His face shows firmness and conviction, his head shows long hair with curls over his shoulders and a laurel wreath. The robes are typical of a courtly atmosphere.

The other side of the coin shows the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Portugal. Above the shield is the king's crown, decorated with pearls, precious stones and gold leaf. At the top, the cross reminds us that João V is king by grace of God. The design of the coat of arms is Italian-influenced and shows the apparatus of the Portuguese court.

In the 18th century, gold coins were an important means of propaganda in the service of politics and diplomacy. It is no wonder that pieces like this circulated within and outside the kingdom's borders."

Coins invaded the markets of English cities and stimulated the economic reasoning of great philosophers such as David Hume and Adam Smith.

"With the issue of the 24 escudos coinage, Portugal had a highly prestigious currency, and Dom João V asserted himself as an absolute monarch, a true projection of the divine majesty."

Source: PLÍNIO PIERRY, JUN. 2019

https://collectprime.com/blog/a-dobra-de-24-escudos-de-d-joao-v/

The Igreja da Madre de Deus (Mother of God), in Xabregas, Lisbon,is an integral part of the former convent with the same name, which today houses the National Tile Museum. Although its structure is Mannerist (16th century), its harmonious decoration is clearly Baroque: gilded woodcarving, paintings and Dutch-made tiles, laid in 1698.

Places to visit

- Igreja de S. Roque, LisboaExplore

- Capelas da Igreja de S. Roque, LisboaExplore

- “A Encomenda Prodigiosa”Explore

- ParamentosExplore

- Museu Nacional dos Coches, LisboaExplore

- Museu Casa da Moeda, LisboaExplore

- Museu do Azulejo, LisboaExplore

- Igreja dos Paulistas (Igreja dos Eremitas de S. Paulo), LisboaExplore

- Igreja do Menino Deus, LisboaExplore

- Igreja do Convento de S. Francisco em S. Salvador, Baía, BrasilExplore

- Capela de São Joao Baptista, LisboaExplore

- Igreja da Madre de Deus, LisboaExplore

- Igrejas Barrocas, LisboaExplore

Continue Exploring

Bibliography

José Jobson Andrade de ARRUDA, «Frotas de 1749: um balanço», Varia Historia, Vol. 15, n. 21, 1999.

Ayres de CARVALHO, D. João V e a Arte do seu tempo, Lisboa, 1960-62

Leonor Freire COSTA, Maria Manuela ROCHA, Rita Martins SOUSA, O Ouro do Brasil, Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda, 2013.

Leonor Freire COSTA, Pedro LAINS, Susana Münch Miranda, An Economic History of Portugal, 1143–2010, Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Suzanne CHANTAL, A Vida Quotidiana em Portugal ao Tempo do Terramoto, Livros do Brasil, s/d.

Adélia Maria Caldas CARREIRA, Lisboa de 1731 a 1833: da desordem à ordem no espaço urbano, Tese de Doutoramento apresentada ao Departamento de História da Arte da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2012.

Angela DELAFORCE, The Lost Library of the King of Portugal, Ad Ilissum, 2019.

Christopher EBERT, «From Gold to Manioc: Contraband Trade in Brazil during the Golden Age, 1700–1750», Colonial Latin American Review, vol. 20, nº 1, 2011, pp. 109-130.

Luís de Bivar GUERRA, Inventário e sequestro da casa de Aveiro em 1759, Lisboa, Edições do Arquivo do Tribunal de Contas, 1952.

James G. LYDON, Fish and Flour for Gold, 1600-1800: Southern Europe in the Colonial Balance of Payments, Library Company of Philadelphia, 2008.

Joaquim Romero MAGALHÃES, «A cobrança do ouro do rei nas Minas Gerais: o fim da capitação – 1741-1750», Tempo, vol. 14, nº 27, 2009.

Nuno Gonçalo MONTEIRO, O crepúsculo dos Grandes (1750-1832), Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, Lisboa, 1998.

João Castel-Branco PEREIRA, «Tronos Rolantes da Monarquia Portuguesa», Oceanos, nº 3, Lisboa, 1990, pp.121-122.

Gustavo de Matos SEQUEIRA, Depois do Terramoto, Subsídios para a História dos Bairros Ocidentais de Lisboa, 4 volumes, 1916-1934.

D. Antonio Caetano de SOUSA, História genealogica da casa real portugueza, Tomo VIII, Na Regia Officina Sylviana e da Academia Real, Lisboa, 1746.

A. J. R. RUSSEL-WOOD, «The Gold Cycle, c. 1690-1750», Colonial Brazil, Bethel, Leslie (ed.), Cambridge University Press, 1987, pp. 190-243.

Show other RFID points

Lisbon 1755 - A city of contrasts

Providências

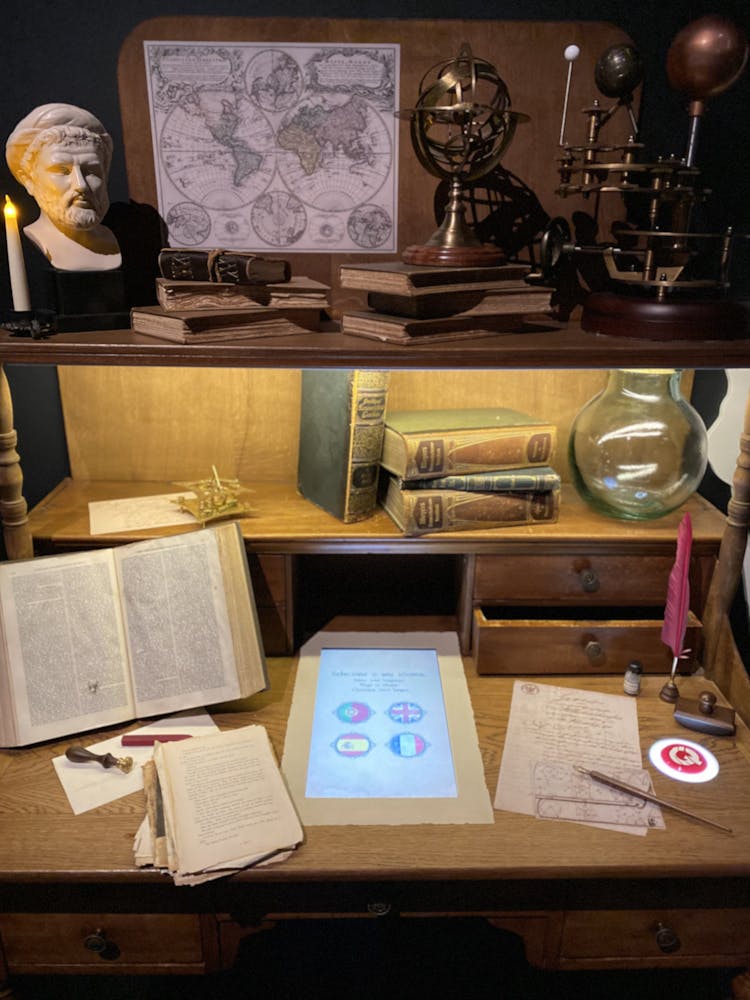

The German merchant

Surgeon Bleeding Barber

The people in the streets

Jesuit book censor Priest

Carpenter accused of bigamy

Tectonic Plates and Moving Plates

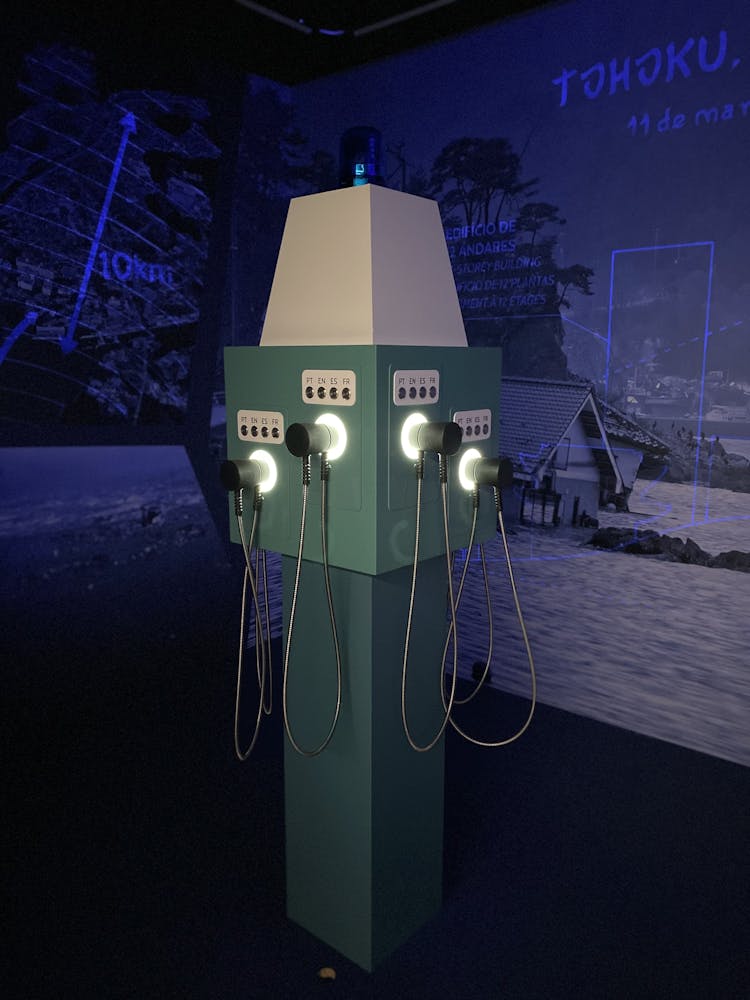

San Francisco and Tohoku

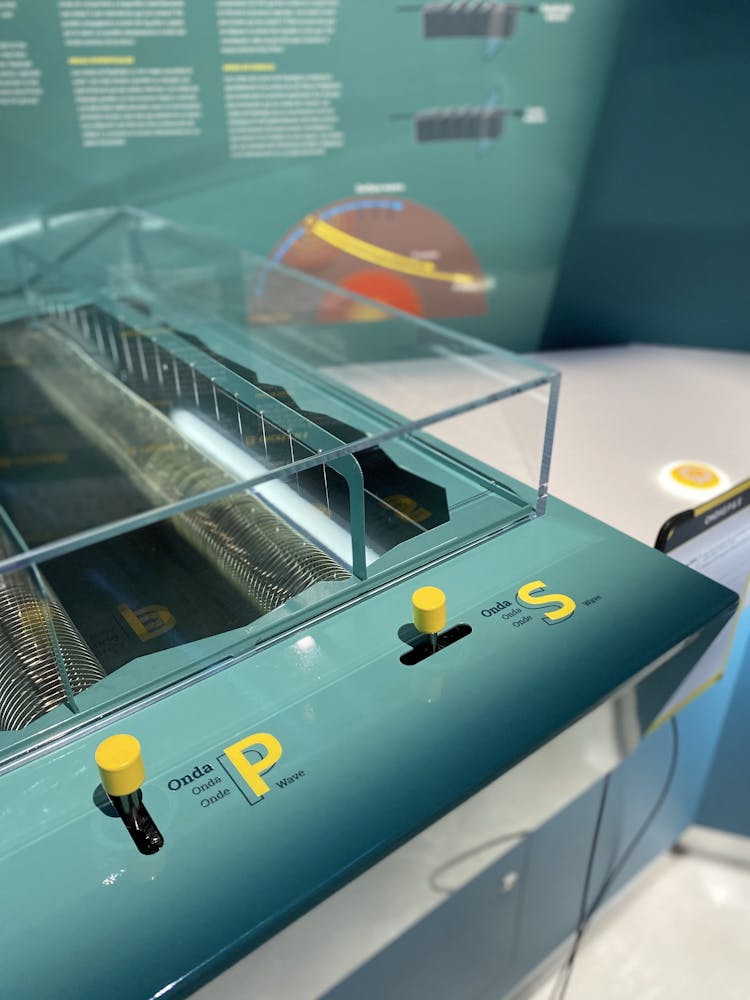

P&S Waves

The Size of an Earthquake

Are we prepared for the next one?

Anti Seismic Constructions

African enslaved woman bought in Lisbon

Continental Drift

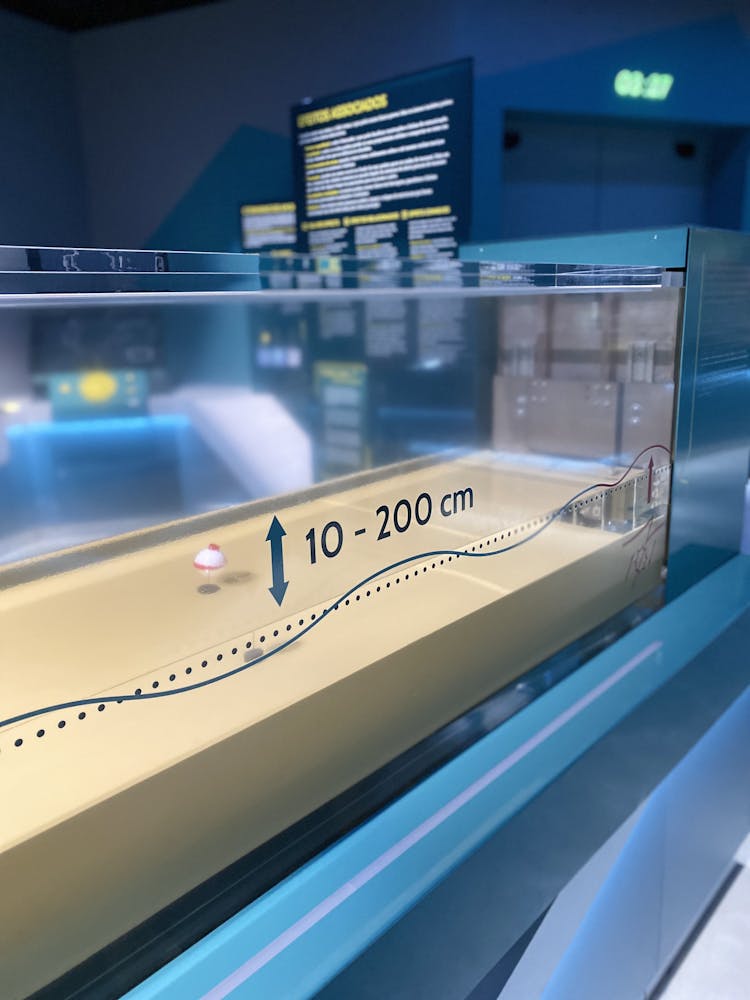

The Tsunami

Seismometer

Richness of the city and gold smuggling

Portugal Tectonics and Lisbon Quakes

How the fires started and propagated

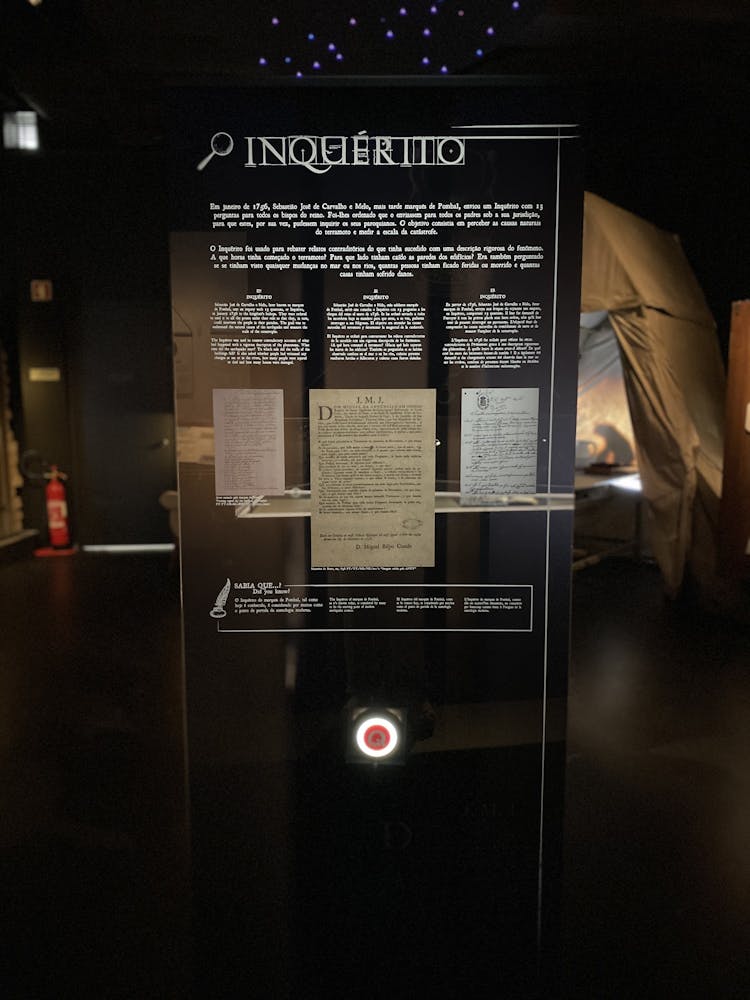

Inquérito

The losses

The three missing documents

Traditional Rite Masses

The connection with the colonized territories

What happened right after the quakes

Presence of the Catholic Church

Related Effects

The King's Ministers

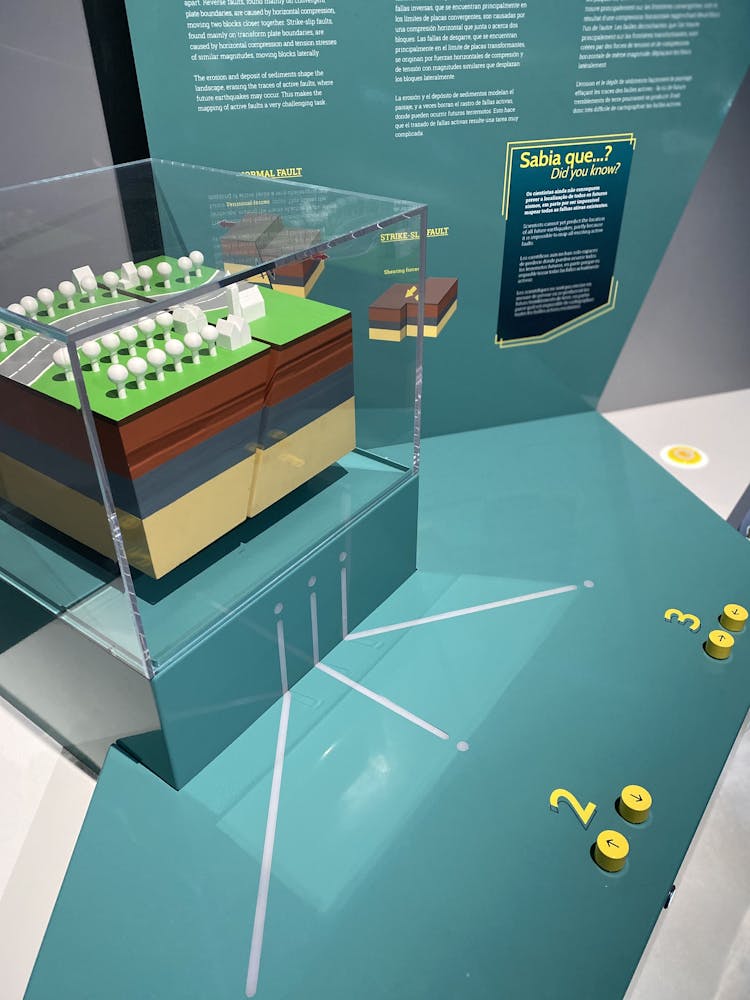

Earthquakes and Faults