Share

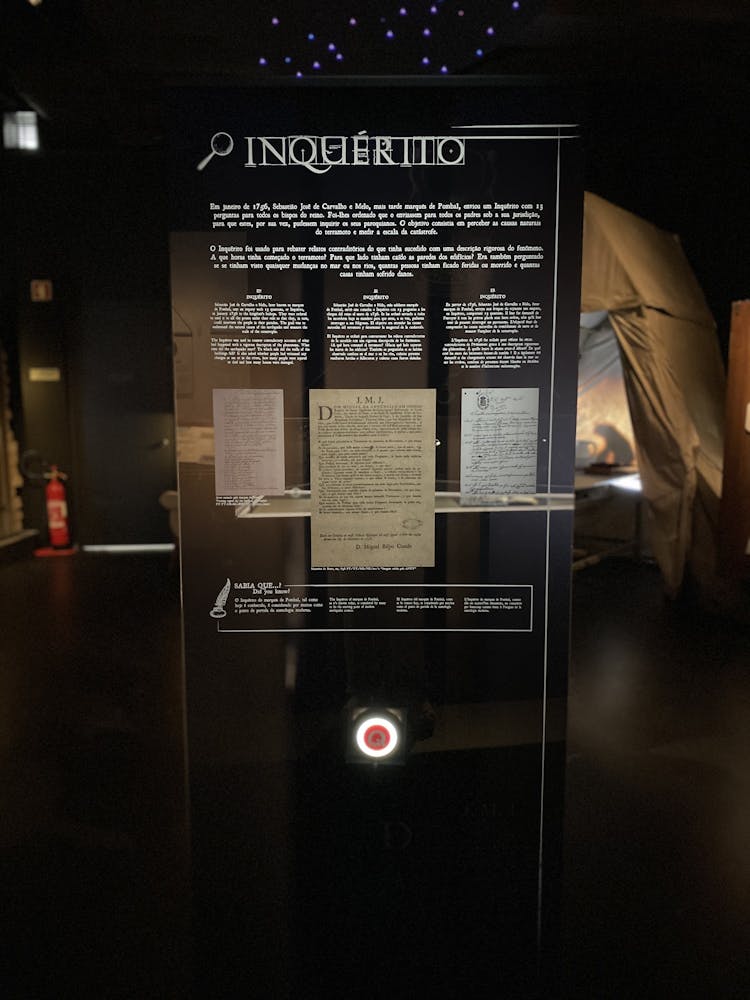

The question in the investigation sent by Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo that generated the most contradictory answers was the one about the time, duration, and quantity of the tremors that occurred that morning. But almost all witnesses were unanimous in describing an apocalyptic scenario in the moments that followed. The sun was covered with dust and all that could be heard were cries imploring God. When the ground found peace, Lisbon had turned into hell. Many clergymen had started to walk through the ruins, confessing the dying and the wounded. They also helped bury the dead and for months, they organised the distribution of food and clothing for the survivors.

Faced with the horror, questions arose about the deeper meaning behind this catastrophe. For the theologians, God had used nature to speak His word. This is how a somewhat confused debate began, mixing scientific explanations with spiritual and philosophical interpretations.

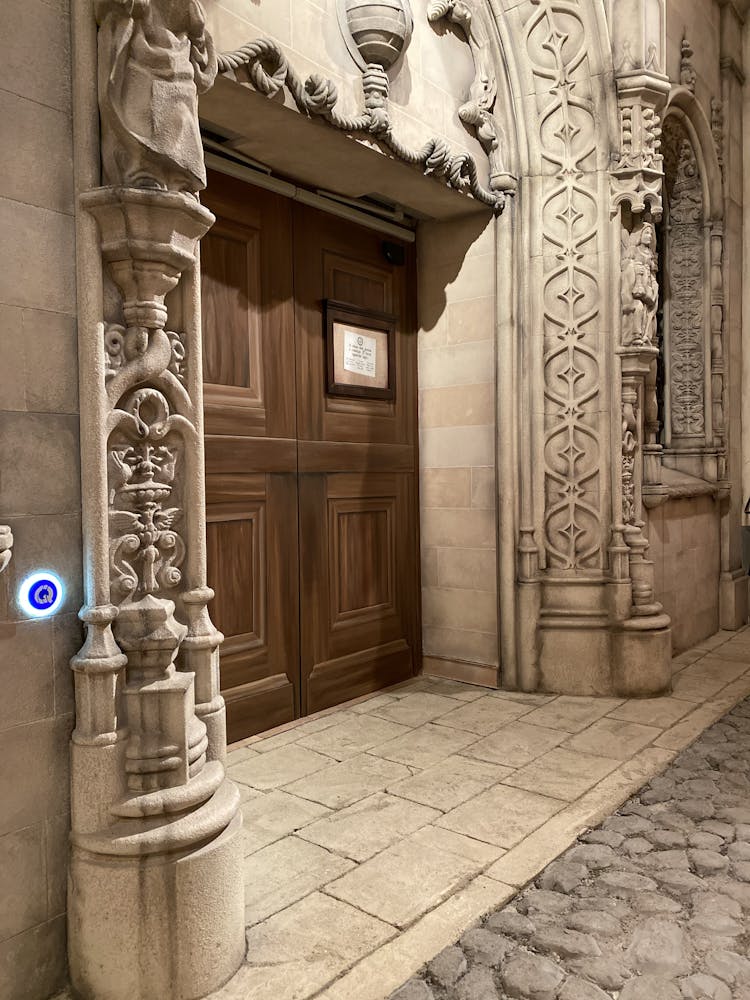

Critical analyses by the Jesuits were partially correct. They did not agree with explanations that were too mechanical or deterministic, such as sulphur and other flammable substances being what generated the shaking. Jesuits were among the most competent in teaching natural philosophy, even though they resisted the more modern theories based on Newton's writings. The importance of the Jesuits in the dissemination of knowledge was due to their historical proximity to power and their influence on the late King John V and his widow, Queen Dowager Mary Anne of Austria.

Some Jesuits, however, adhered to the idea that the destruction was caused by the actions of man. In his famous work published in 1756, Judgment on the true cause of the earthquake that struck the Court of Lisbon on 1 November 1755, Gabriel Malagrida accused the inhabitants of Lisbon of having been the “murderers” of so many innocent people. According to the spiritual vision, a rare event could only have a prodigious and theological explanation. The ecclesiastics most attached to a religious vision of reality emphasised the importance of dealing with the suffering of the living, criticising those who claimed to have access to a demonstration of causes. However, at that time, this position began to be in logical contradiction with the growing number of authors leaning towards a scientific explanation of earthquakes.

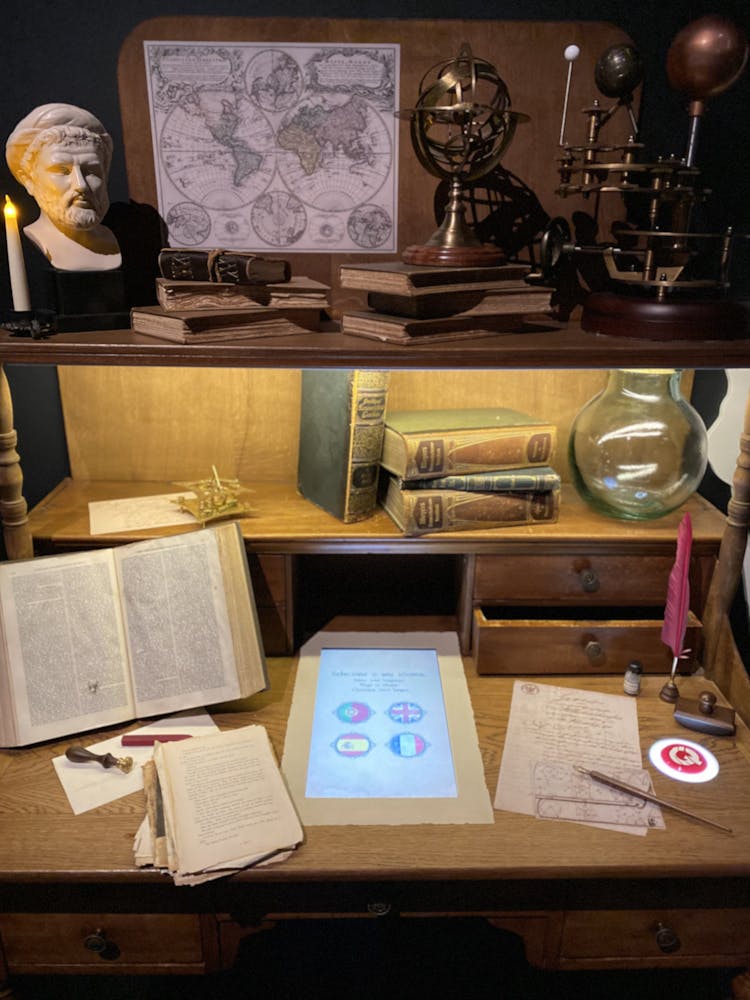

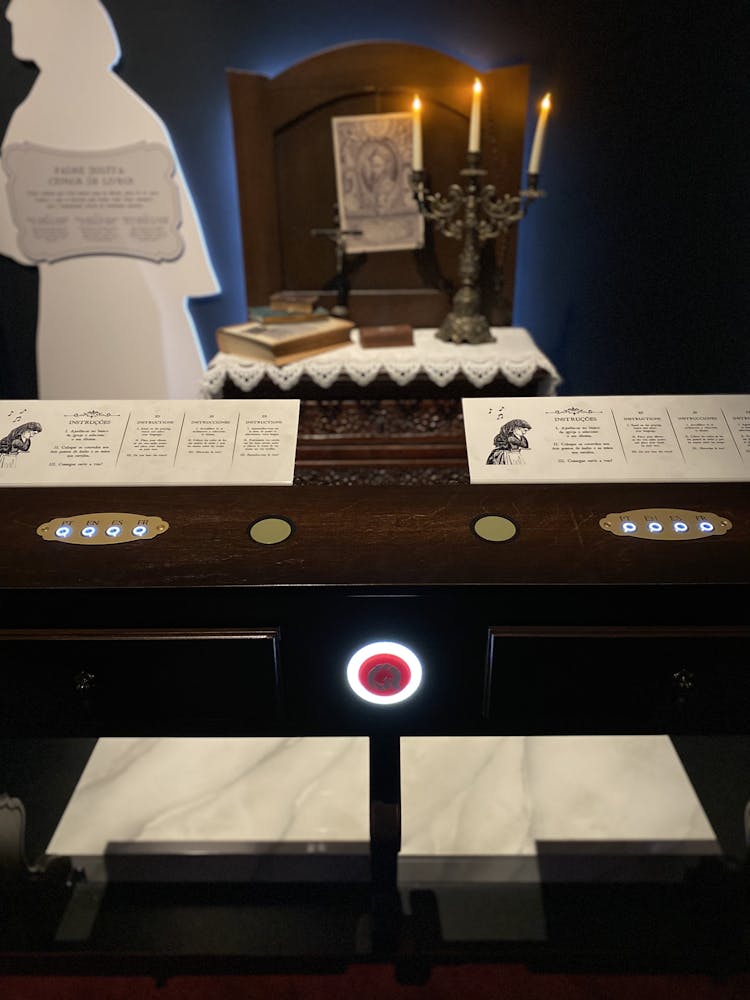

IN SALA DOS CONTOS:

Italian Jesuit priest who spent many years living in Brazil before coming to Lisbon. He is interested in how God speaks to Man through natural phenomena. He tells:

God chose me to be a priest, and I became a Jesuit. I am fascinated by how God uses natural phenomena to speak to men. That’s why I have been reading about the causes and origins of the earthquake.

With the mercy of God, I survived the shakes. What had started as a beautiful day became a scene from Hell. Roof tiles were blown away like feathers, and dust covered the sunlight. I saw survivors almost entirely smothered in grime, people shouting out to God for mercy, mothers carrying dead children, and on every corner, mutilated, unrecognisable corpses. It was as if Judgement Day had finally arrived.

My brothers—the priests and friars who could still walk—went through the streets to help rescue the wounded, but also to administer last rites to the dying, praying with them. Many congregations—the ones still standing—have opened their doors and are housing the sick, calling for surgeons and doctors, burying the dead, and organising shelter and food for the living. In just one day, the Augustinian friars alone have killed 160 chickens to feed the sick and injured! May God bless their charitable hearts!

Could such a calamity, such a rare event, be only a sign from God? Or is the mystery of nature larger than what we have imagined? The only thing left to do is take care of the suffering, as all the explanations for the earthquake I have been reading about seem to be full of fantasy and very incomplete. Nonsense! How can we reduce this horror to a simple Inquiry? Others explain the destruction by the sinful actions of men: anger, lust, vanity, and other sinful vices. Father Malagrida claims that these are the real “murderers” of so many innocent people. But maybe Father Malagrida should be more careful, rumour goes that he will be arrested, despite the intervention of the widow-queen.

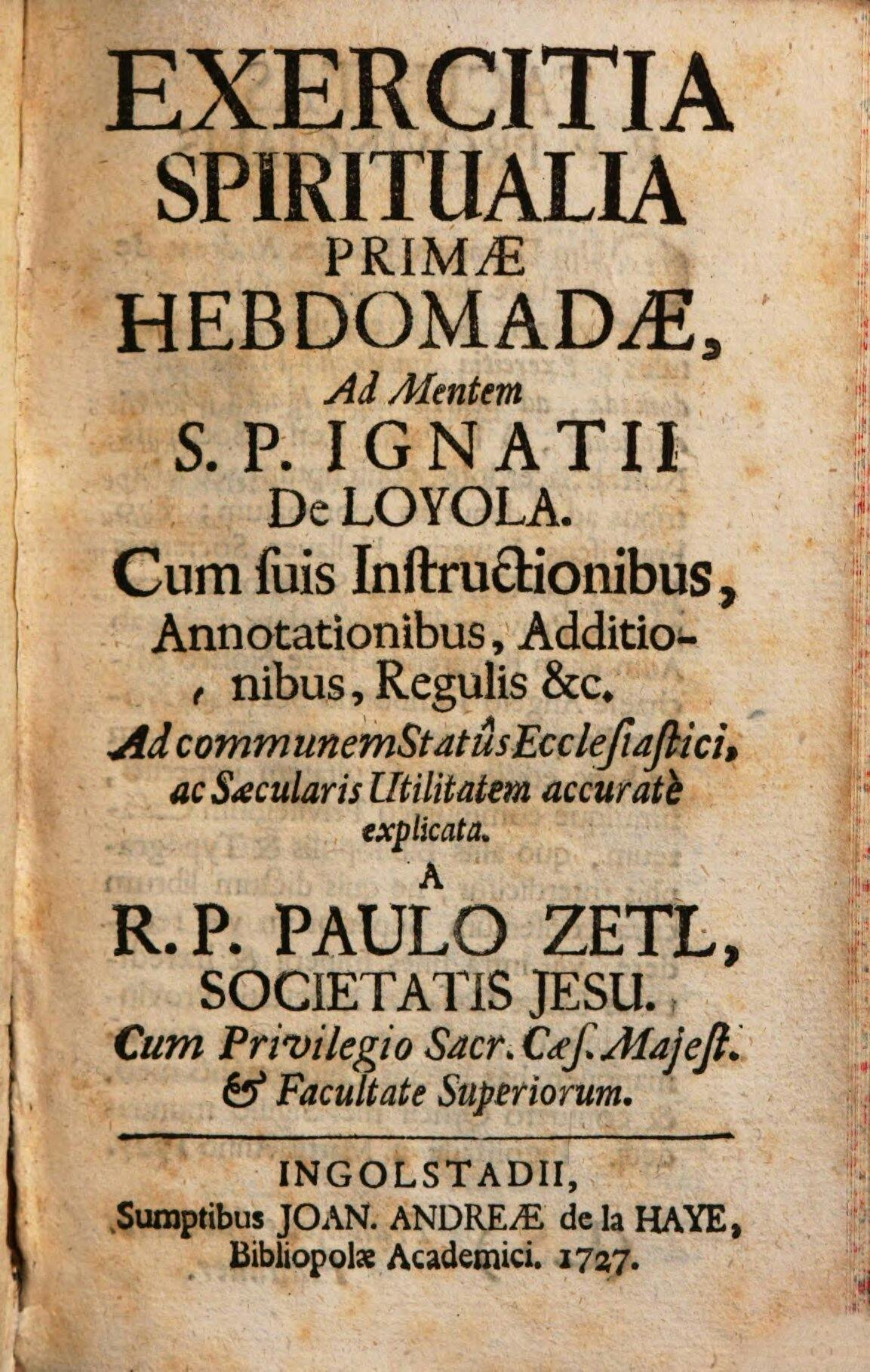

The Spiritual Exercises, written by St Ignatius of Loyola, first published in 1548, would have many re-editions in the following centuries. This manual of private devotion and meditation on the suffering of Jesus Christ was to accompany religious and lay people (ordinary people), in silent retreats intended to exercise, from a practical point of view, the correction of behaviour. Inspired by stoic therapies and oriental monasticism, some editions had spaces with the days of the week on which to record the number of failures of attention and control. This made it possible to measure the effects of the Exercises, hoping for a decrease in the number of errors or deviations. Given the influence of the Society of Jesus in the Portuguese aristocracy, the Spiritual Exercises accompanied the attempt of spiritual re-establishment after the Earthquake.

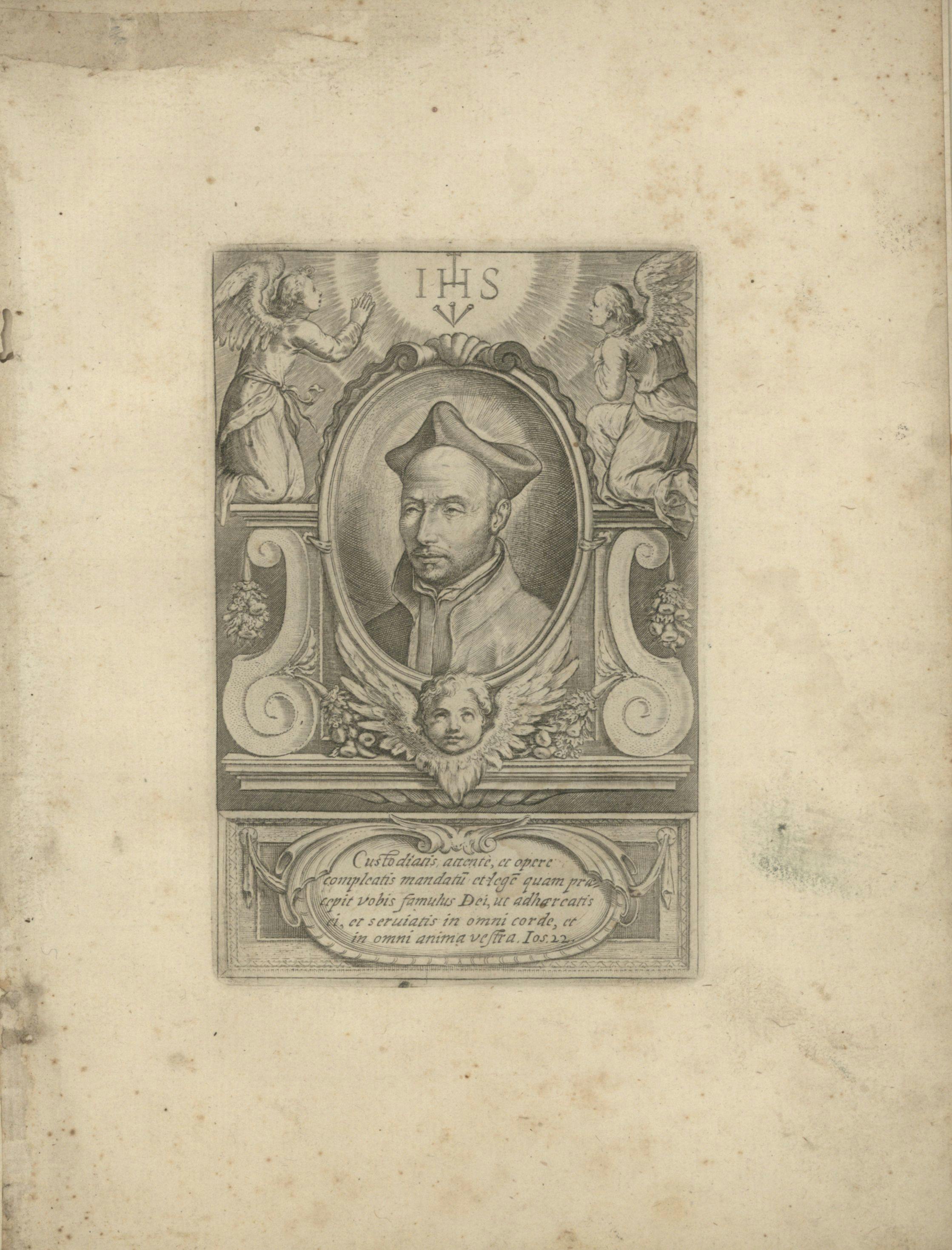

Image taken from a three-part biography of Saint Ignatius Loyola (1491 – 1556) by Giovanni Pietro Maffei, bound together with eighty plates by an unidentified engraver illustrating the life of the founder of the Society of Jesus. Printed in 1622, the year of Ignatius’s canonization by Pope Gregory XV, the plates provide a fascinating visual chronicle of the saint’s work and the time in which he lived.

Black and white buril engraving. Date and place of publication: Paris? s.n., between 1761 and 1777? - Probable date, considering the condemnation of Malagrida and the deposition of the Marquis of Pombal (the authors defend themselves under anonymity).

Gabriel Malagrida (Menaggio, Milan, 18 September 1689 - Lisbon, 21 September 1761) was an Italian Jesuit priest. After many decades in Brazil, he came to Lisbon, where he maintained a close relationship with the royal family. After the 1755 earthquake, he published a booklet: "Judgement of the true cause of the earthquake that the court of Lisbon suffered on November 1st 1755". It was a theologically very conservative text, censuring the frequenting of theatres, gambling houses, the "immodest dances and the most obscene comedies", amusements and even bullfighting, customs presented as the spiritual cause of the Earthquake. Malagrida would have offered copies of the booklet to the royal family and to Sebastião José de carvalho e Melo himself, who understood the gesture as a provocation. By intervention of the apostolic nuncio, instigated by Carvalho e Melo, and by order of the provincial of the Society of Jesus, he was banished to Setúbal in 1756. After the expulsion of the Jesuits, following the 1758 attempt, he was arrested at Junqueira Prison in January 1759. The sentence of the Inquisition included the connection to the trial of the Távoras, involved in a conspiracy against the king. Malagrida was considered a heretic, a false prophet and author of blasphemies. After being garroted in a public ceremony, he was burned on 21 September 1761. His pamphlets were censored, by edict of the Mesa Censoria of April 30, and burned in Praça do Comércio, on May 8, 1771 - ten years after its author's death.

Continue Exploring

Bibliography

Isabel Maria Barreira de CAMPOS, O grande terramoto (1755), Pareceria, 1998.

Arnaldo Pinto CARDOSO, O terrível terramoto da cidade que foi Lisboa-correspondência do Núncio Fillipo Acciaiuoli: Arquivos secretos do Vaticano, Alétheia, 2013.

Destruição de Lisboa, e famosa desgraça, que padeceu no primeiro de Novembro de 1755, Lisboa, 1756.

António FERRÃO, O Marquês de Pombal e a expulsão dos Jesuítas (1759), Coimbra, 1932.

José Eduardo FRANCO, «O “Terramoto” Pombalino e a Campanha de desjesuitização de Portugal», Lusitânia Sacra, 2ª série, 18, 2006, pp. 147-218.

Gabriel MALAGRIDA, Juízo da Verdadeira Causa do Terremoto que Padeceo a Corte de Lisboa no Primeiro de Novembro de 1755, Lisboa, Manoel Soares, 1756.

Mark MOLESKY, “This Gulf of Fire: The Great Lisbon Earthquake, or Apocalypse in the Age of Science and Reason”, 2016, Penguin Random House

Paulo MURY, História de Gabriel Malagrida da Companhia de Jesus, Livraria Editora de Matos Moreira, 1875.

Marcus ODILON, A vida e a obra do Padre Malagrida no Brasil, João Pessoa, 1990.

José Pedro PAIVA, Baluartes da fé e da disciplina. O enlace entre a Inquisição e os bispos em Portugal (1536-1750), Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 2011.

António Pereira da SILVA, A questão do sigilismo em Portugal no século XVIII, História, religião e política nos reinados de D. João V e de D. José I, Editorial Franciscana, 1964.

António Nunes Ribeiro SANCHES, Tratado da Conservaçam da Saúde dos Povos, Obra util e igualmente necessaria a os Magistrados; Capitaens Generais, Capitaens de Mar, e Guerra, Prelados, Abbadessas, Medicos, e Pays de Familias/Com Hum Apendix/ Consideraçoins sobre os Terramotos, com a noticia dos mais consideraveis, de que fas mençaô a Historia, e dos ultimos que se sintiraô na Europa desde o I de Novembro 1755, Paris, 1756.

R. K. REEVES, The Lisbon Earthquake of 1755: Confrontation between the Church and the Enlightenment in Eighteenth-Century Portugal, Tese de doutoramento, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pensilvânia, 2000.

Refutaçam de alguns erros que o falso, e fantastico nome de profecias, ou vaticinios, se divulgaram e espalharam ao presente, aonde com toda a brevidade, e clareza se mostra sua insubsistência e falsidade, Officina de Domingos Rodrigues, 1756.

Jose Acursio de TAVARES, Verdade vindicada ou resposta a huma carta escrita em Coimbra, em que se dá noticia do lamentável sucesso de Lisboa, no dia I de Novembro de 1755, Lisboa, Officina de Miguel Manescal da Costa, 1756.

Rui TAVARES, O Censor Iluminado - Ensaio sobre o Séc. XVIII e a Revolução Cultural do Pombalismo, Tinta da China, 2018.

José VERÍSSIMO, Pombal, os Jesuítas e o Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 1961.

Luís António VERNEY, Verdadeiro metodo de estudar, para ser util à República, e à Igreja: proporcionado ao estilo, e necesidade de Portugal exposto em varias cartas, escritas polo R.P. Barbadinho do Congregasam de Italia à R. P. Doutor na Universidade de Coimbra, Tomo Segundo, Oficina de Antonio Balle, 1747.

Show other RFID points

Lisbon 1755 - A city of contrasts

Providências

The German merchant

Surgeon Bleeding Barber

The people in the streets

Jesuit book censor Priest

Carpenter accused of bigamy

Tectonic Plates and Moving Plates

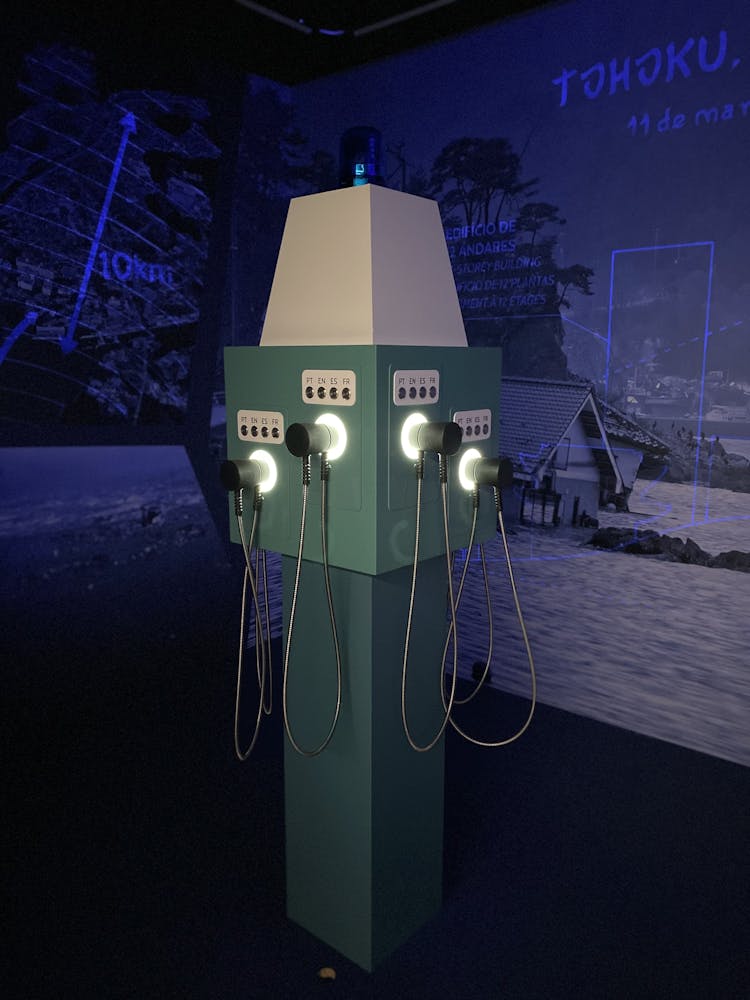

San Francisco and Tohoku

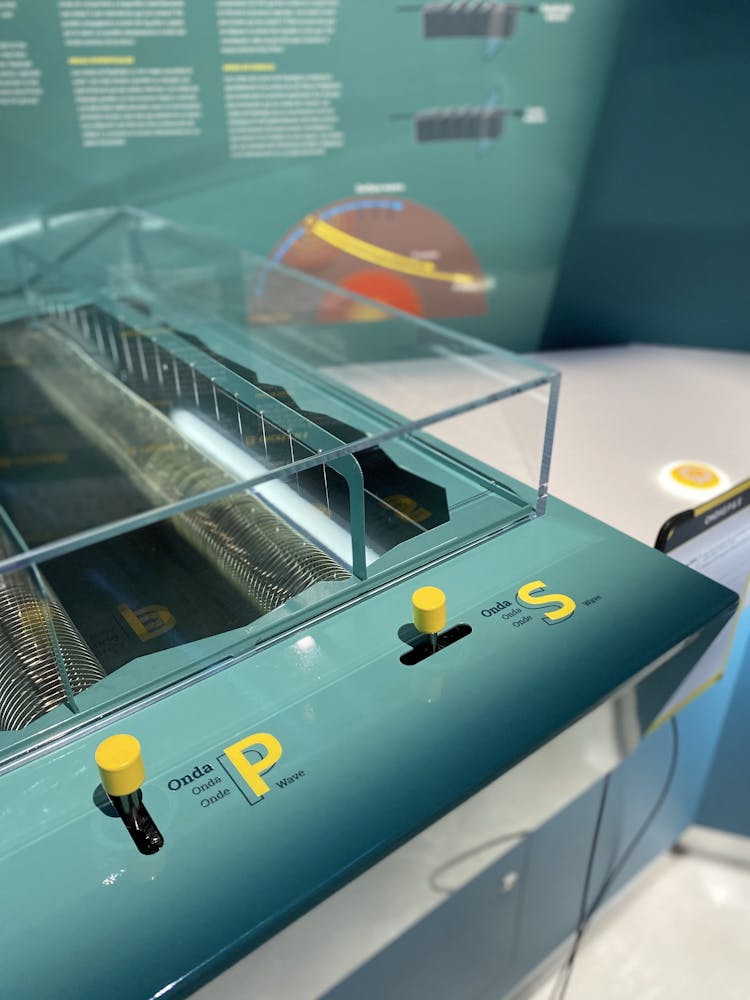

P&S Waves

The Size of an Earthquake

Are we prepared for the next one?

Anti Seismic Constructions

African enslaved woman bought in Lisbon

Continental Drift

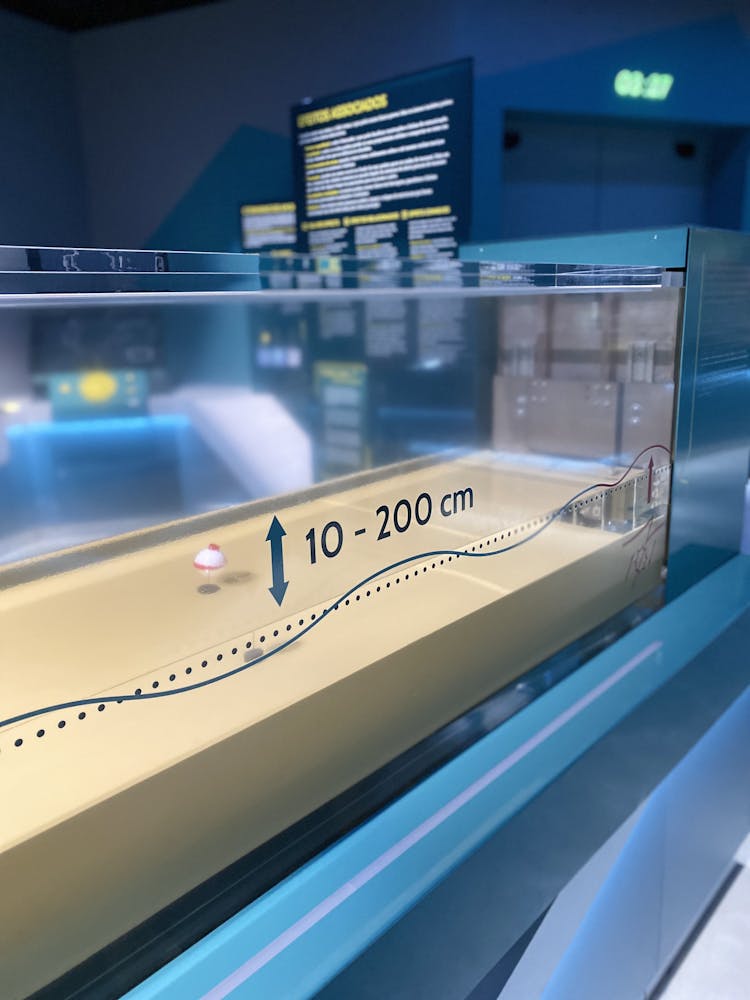

The Tsunami

Seismometer

Richness of the city and gold smuggling

Portugal Tectonics and Lisbon Quakes

How the fires started and propagated

Inquérito

The losses

The three missing documents

Traditional Rite Masses

The connection with the colonized territories

What happened right after the quakes

Presence of the Catholic Church

Related Effects

The King's Ministers

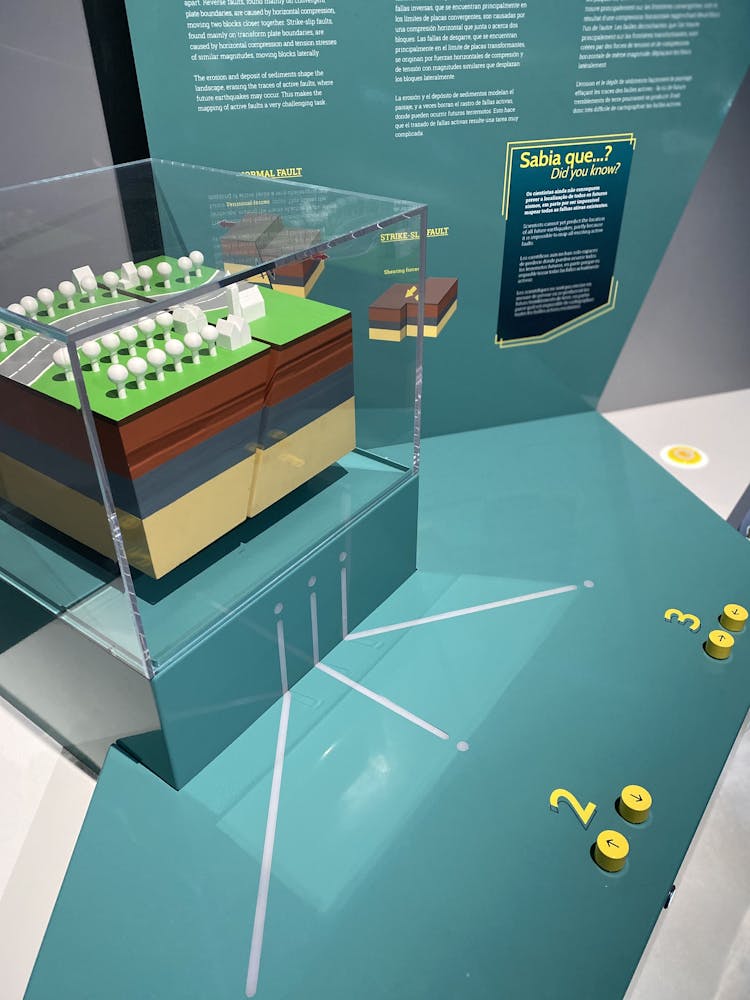

Earthquakes and Faults